Abstract

Deflection of light by gravity was predicted by General Relativity and observationally confirmed in 1919. In the following decades, various aspects of the gravitational lens effect were explored theoretically. Among them were: the possibility of multiple or ring-like images of background sources, the use of lensing as a gravitational telescope on very faint and distant objects, and the possibility of determining Hubble’s constant with lensing. It is only relatively recently, (after the discovery of the first doubly imaged quasar in 1979), that gravitational lensing has became an observational science. Today lensing is a booming part of astrophysics.

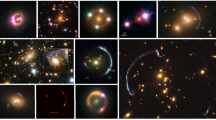

In addition to multiply-imaged quasars, a number of other aspects of lensing have been discovered: For example, giant luminous arcs, quasar microlensing, Einstein rings, galactic microlensing events, arclets, and weak gravitational lensing. At present, literally hundreds of individual gravitational lens phenomena are known.

Although still in its childhood, lensing has established itself as a very useful astrophysical tool with some remarkable successes. It has contributed significant new results in areas as different as the cosmological distance scale, the large scale matter distribution in the universe, mass and mass distribution of galaxy clusters, the physics of quasars, dark matter in galaxy halos, and galaxy structure. Looking at these successes in the recent past we predict an even more luminous future for gravitational lensing.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Within the last 20 years, gravitational lensing has changed from being considered a geometric curiosity to a helpful and in some ways unique tool of modern astrophysics. Although the deflection of light at the solar limb was very successfully hailed as the first experiment to confirm a prediction of Einstein’s theory of General Relativity in 1919, it took more than half a century to establish this phenomenon observationally in some other environment. By now almost a dozen different realizations of lensing are known and observed, and surely more will show up.

Gravitational lensing — the attraction of light by matter — displays a number of attractive features as an academic discipline. Its principles are very easy to understand and to explain due to its being a geometrical effect. Its ability to produce optical illusions is fascinating to scientists and laypeople alike. And — most importantly of course — its usefulness for a number of astrophysical problems makes it an attractive tool in many branches of astronomy. All three aspects will be considered below.

In its almost two decades of existence as an observational branch of astrophysics, the field of gravitational lensing has been continuously growing. Every few years a new realisation of the phenomenon is discovered. Multiple quasars, giant luminous arcs, quasar microlensing, Einstein rings, galactic microlensing, weak lensing, galaxy-galaxy lensing open up very different regimes for the gravitational telescope. This trend is reflected in the growing number of people working in the field. In Figure 1 the number of publications in scientific journals that deal with gravitational lensing is plotted over time. It is obvious that lensing is booming as an area of investigation.

Number of papers on gravitational lensing per year over the last 35 years. This diagram is based on the October 1997 version of the lensing bibliography compiled by Pospieszalska-Surdej, Surdej and Veron [108]. The apparent drop after the year 1995 does not reflect a drop in the number of papers, but rather the incompleteness of the survey.

Although there had been a slight sense of disappointment in the astronomical community a few years ago because lensing had not yet solved all the big problems of astrophysics (e.g. determination of the Hubble constant; nature of dark matter; physics/size of quasars), this feeling has apparently reversed. With its many applications and quantitative results, lensing has started to fulfill its astrophysical promises.

We shall start with a brief look back in time and mention some historic aspects of light deflection and lensing in Section 2. We then attempt to explain the basic features of gravitational lensing quantitatively, deriving some of the relevant equations (Section 3). A whole variety of lensing observations and phenomena which curved space-time provides for us is presented in Section 4, for example, multiple versions of quasars, gigantically distorted images of galaxies, and highly magnified stars. Additionally, we explain and discuss the astrophysical applications of lensing which show the use of this tool. This section will be the most detailed one. Finally, in the concluding Section 5 we try to extrapolate and speculate about the future development of the field.

By design, this review can only touch upon the issues relevant in the astrophysical field of gravitational lensing. This article should serve as a guide and general introduction and provide a number of useful links and references. It is entirely impossible to be complete in any sense. So the selection of topics and literature necessarily is subjective. Since the idea of the “Living Reviews” is to be regularly updated, I ask all authors whose work I may not have represented properly to contact me so that this can be corrected in the next version of this article.

• Going further. Since this article in no way can cover the whole field of lensing and its applications, we list here a number of books, proceedings and other (partly complementary) review articles on the subject of gravitational lensing.

The textbook by Schneider, Ehlers, and Falco [169] contains the most comprehensive presentation of gravitational lensing. A new edition is underway. The book by Bliokh and Minakov [29] on gravitational lensing is still only available in Russian. A new book currently in press by Petters, Levine, and Wambsganss [140] treats mainly the mathematical aspects of lensing, in particular its applications to singularity theory.

The contributions to the most important conferences on gravitational lensing in the last few years have all been published: Swings [181] edited the Proceedings on the first conference on lensing in Liège in 1983. Moran et al. [126] are the editors of the MIT workshop on lensing in 1988. Also see, Mellier et al. [121] of the Toulouse conference in 1989; Kayser et al. [91] of the Hamburg meeting in 1991; Surdej et al. [180] of the Liège conference in 1993; and Kochanek and Hewitt [103] of the IAU Symposium 173 in Melbourne in 1995. Online proceedings of a few smaller and more recent meetings also exist. See: Jackson [81] of the Jodrell Bank Meeting “Golden Lenses” in 1997.

A number of excellent reviews on gravitational lensing also exist. Blandford and Kochanek [24] give a nice introduction on the theory of lensing. The optical aspects of lensing are derived elegantly in [25]. The presentation of Blandford and Narayan [28] emphasizes in particular the cosmological applications of gravitational lensing. The review by Refsdal and Surdej [153] contains a section on optical model lenses that simulate the lensing action of certain astrophysical objects. A recent review article by Narayan and Bartelmann [128] summarizes in a very nice and easy-to-understand way the basics and the latest in the gravitational lens business. In the sections below, some more specific review articles will be mentioned.

2 History of Gravitational Lensing

The first written account of the deflection of light by gravity appeared in the “Berliner Astronomisches Jahrbuch auf das Jahr 1804” in an article entitled: “Ueber die Ablenkung eines Lichtstrals von seiner geradlinigen Bewegung, durch die Attraktion eines Weltkörpers, an welchem er nahe vorbeigeht” (“On the Deflection of a Light Ray from its Straight Motion due to the Attraction of a World Body which it Passes Closely”) [177]. Johann Soldner — a German geodesist, mathematician and astronomer then working at the Berlin Observatory — explored this effect and inferred that a light ray close to the solar limb would be deflected by an angle \({\tilde \alpha}\) = 0.84 arcsec. It is very interesting to read how carefully and cautiously he investigated this idea and its consequences on practical astronomy.

In the year 1911 — more than a century later — Albert Einstein [41]directly addressed the influence of gravity on light (“über den Einfluß der Schwerkraft auf die Ausbreitung des Lichtes” (“On the Influence of Gravity on the Propagation of Light”). At this time, the General Theory of Relativity was not fully developed. This is the reason why Einstein obtained — unaware of the earlier result — the same value for the deflection angle as Soldner had calculated with Newtonian physics. In this paper, Einstein found \({\tilde \alpha}\) = 2GM⊙/c2R⊙ = 0.83 arcsec for the deflection angle of a ray grazing the sun (here M⊙ and R⊙ are the mass and the radius of the sun, c and G are the velocity of light and the gravitational constant, respectively). Einstein emphasized his wish that astronomers investigate this question (“Es wäre dringend zu wünschen, daß sich Astronomen der hier aufgerollten Frage annähmen, auch wenn die im vorigen gegebenen Überlegungen ungenügend fundiert oder gar abenteuerlich erscheinen sollten.” (“It would be very desirable that astronomers address the question unrolled here, even if the considerations should seem to be insufficiently founded or entirely speculative.”) Recently it was discovered that Einstein had derived the lens equation, the possibility of a double image and the magnifications of the images in a notebook in the year 1912 [155]. In 1913 Einstein even contacted the director of the Mt. Wilson Observatory, George Ellery Hale, and asked him whether it would be possible to measure positions of stars near the sun during the day in order to establish the deflection effect of the sun.

See [52] to view a facsimile of a letter Einstein wrote to G.E. Hale on October 14, 1913. In the letter, Einstein asked Hale whether it would be possible to determine the light deflection at the solar limb during the day. However, there was a “wrong” value of the deflection angle in a sketch Einstein included in the letter.

There actually were plans to test Einstein’s wrong prediction of the deflection angle during a solar eclipse in 1914 on the Russian Crimea peninsula. However, when the observers were already in Russia, World War I broke out and they were captured by Russian soldiers [33]. So, fortunately for Einstein, the measurement of the deflection angle at the solar limb had to be postponed for a few years.

With the completion of the General Theory of Relativity, Einstein was the first to derive the correct deflection angle \({\tilde \alpha}\) of a light ray passing at a distance r from an object of mass M as

where G is the constant of gravity and c is the velocity of light. The additional factor of two (compared to the “Newtonian” value) reflects the spatial curvature (which is missed if photons are just treated as particles). With the solar values for radius and mass Einstein obtained [53, 54]:

It is common wisdom now that the determination of this value to within 20% during the solar eclipse in 1919 by Arthur Eddington and his group was the second observational confirmation of General Relativity [48] and the basis of Einstein’s huge popularity starting in the 1920s. (The first one had been the explanation of Mercury’s perihelion shift.) Recently, the value predicted by Einstein was confirmed to an accuracy better than 0.02% [107].

In the following decades, light deflection or gravitational lensing was only very rarely the topic of a research paper: In 1924, Chwolson [40] mentioned the idea of a “fictitous double star” and the mirror-reversed nature of the secondary image. He also mentioned the symmetric case of star exactly behind star, resulting in a circular image. Einstein also reported in 1936 about the appearance of a “luminous circle” for perfect alignment between source and lens [55], and of two magnified images for slightly displaced positionsFootnote 1. Today such a lens configuration is called “Einstein-ring”, although more correctly it should be called “Chwolson-ring”. Influenced by Einstein, Fritz Zwicky [210, 211] pointed out in 1937 that galaxies (“extragalactic nebulae”) are much more likely to be gravi-tationally lensed than stars and that one can use the gravitational lens effect as a “natural telescope”.

In the 1960s, a few partly independent theoretical studies showed the usefulness of lensing for astronomy [95, 111, 112, 123, 148, 149]. In particular, Sjur Refsdal derived the basic equations of gravitational lens theory and subsequently showed how the gravitational lens effect can be used to determine Hubble’s constant by measuring the time delay between two lensed images. He followed up this work with interesting applications of lensing [151, 150, 152]. The mathematical foundation of how a light bundle is distorted on its passage through the universe had been derived in the context of gravitational radiation even before [159].

Originally, gravitational lensing was discussed for stars or for galaxies. When quasars were discovered in the 1960s, Barnothy [15] was the first to connect them with the gravitational lens effect. In the late 60s/early 70s, a few groups and individuals explored various aspects of lensing further, for example, statistical effects of local inhomogeneities on the propagation of light [74, 75, 145]; lensing applied to quasars and clusters of galaxies [43, 132, 160]; development of a formalism for transparent lenses [31, 41]; and the effect of an inhomogeneous universe on the distance-redshift relations [47].

But only in 1979 did the whole field receive a real boost when the first double quasar was discovered and confirmed to be a real gravitational lens by Walsh, Carswell & Weymann [194]. This discovery, and the development of lensing since then, will be described in Section 4.

3 Basics of Gravitational Lensing

The path, the size and the cross section of a light bundle propagating through spacetime in principle are affected by all the matter between the light source and the observer. For most practical purposes, we can assume that the lensing action is dominated by a single matter inhomogeneity at some location between source and observer. This is usually called the “thin lens approximation”: All the action of deflection is thought to take place at a single distance. This approach is valid only if the relative velocities of lens, source and observer are small compared to the velocity of light v ≪ c and if the Newtonian potential is small |Φ| ≪ c2. These two assumptions are justified in all astronomical cases of interest. The size of a galaxy, e.g., is of order 50 kpc, even a cluster of galaxies is not much larger than 1 Mpc. This “lens thickness” is small compared to the typical distances of order few Gpc between observer and lens or lens and background quasar/galaxy, respectively. We assume that the underlying spacetime is well described by a perturbed Friedmann-Robertson-Walker metricFootnote 2:

3.1 Lens equation

The basic setup for such a simplified gravitational lens scenario involving a point source and a point lens is displayed in Figure 2. The three ingredients in such a lensing situation are the source S, the lens L, and the observer O. Light rays emitted from the source are deflected by the lens. For a point-like lens, there will always be (at least) two images Si and S2 of the source. With external shear — due to the tidal field of objects outside but near the light bundles — there can be more images. The observer sees the images in directions corresponding to the tangents to the real incoming light paths.

In Figure 3 the corresponding angles and angular diameter distances DL, DS, DLS are indicatedFootnote 3. In the thin-lens approximation, the hyperbolic paths are approximated by their asymptotes. In the circular-symmetric case the deflection angle is given as

where M(ξ) is the mass inside a radius ξ. In this depiction the origin is chosen at the observer. From the diagram it can be seen that the following relation holds:

(for θ, β, \({\tilde \alpha}\) ≪ 1; this condition is fulfilled in practically all astrophysically relevant situations). With the definition of the reduced deflection angle as α(θ) = (DLS/DS) \({\tilde \alpha}\) (θ), this can be expressed as:

This relation between the positions of images and source can easily be derived for a non-symmetric mass distribution as well. In that case, all angles are vector-valued. The two-dimensional lens equation then reads:

The relation between the various angles and distances involved in the lensing setup can be derived for the case \({\tilde \alpha}\) ≪ 1 and formulated in the lens equation (6).

3.2 Einstein radius

For a point lens of mass M, the deflection angle is given by Equation (4). Plugging into Equation (6) and using the relation ξ = DLθ (cf. Figure 3), one obtains:

For the special case in which the source lies exactly behind the lens (β = 0), due to the symmetry a ring-like image occurs whose angular radius is called Einstein radius θE:

The Einstein radius defines the angular scale for a lens situation. For a massive galaxy with a mass of M = 1012M⊙ at a redshift of zL = 0.5 and a source at redshift zS = 2.0, (we used here H = 50 km sec-1 Mpc-1 as the value of the Hubble constant and an Einstein-deSitter universe), the Einstein radius is

(note that for cosmological distances in general DLS ≠ DS - DL!). For a galactic microlensing scenario in which stars in the disk of the Milky Way act as lenses for bulge stars close to the center of the Milky Way, the scale defined by the Einstein radius is _

An application and some illustrations of the point lens case can be found in Section 4.7 on galactic microlensing.

3.3 Critical surface mass density

In the more general case of a three-dimensional mass distribution of an extended lens, the density ρ(⃗r) can be projected along the line of sight onto the lens plane to obtain the two-dimensional surface mass density distribution Σ(⃗ξ), as

Here ⃗r is a three-dimensional vector in space, and ⃗ξ is a two-dimensional vector in the lens plane. The two-dimensional deflection angle \(\vec {\tilde \alpha}\) is then given as the sum over all mass elements in the lens plane:

For a finite circle with constant surface mass density Σ the deflection angle can be written:

With ξ = DLθ this simplifies to

With the definition of the critical surface mass density Σcrit as

the deflection angle for a such a mass distribution can be expressed as

The critical surface mass density is given by the lens mass M “smeared out” over the area of the Einstein ring: Σcrit = M/(R 2E π), where RE = θEDL. The value of the critical surface mass density is roughly Σcrit ≈ 0.8 g cm-2 for lens and source redshifts of zL = 0.5 and zS = 2.0, respectively. For an arbitrary mass distribution, the condition Σ > Σcrit at any point is sufficient to produce multiple images.

3.4 Image positions and magnifications

The lens equation (6) can be re-formulated in the case of a single point lens:

Solving this for the image positions θ one finds that an isolated point source always produces two images of a background source. The positions of the images are given by the two solutions:

The magnification of an image is defined by the ratio between the solid angles of the image and the source, since the surface brightness is conserved. Hence the magnification μ is given as

In the symmetric case above, the image magnification can be written as (by using the lens equation):

Here we defined u as the “impact parameter”, the angular separation between lens and source in units of the Einstein radius: u = β/θE. The magnification of one image (the one inside the Einstein radius) is negative. This means it has negative parity: It is mirror-inverted. For β → 0 the magnification diverges. In the limit of geometrical optics, the Einstein ring of a point source has infinite magnificationFootnote 4! The sum of the absolute values of the two image magnifications is the measurable total magnification μ:

Note that this value is (always) larger than oneFootnote 5! The difference between the two image magnifications is unity:

3.5 (Non-)Singular isothermal sphere

A handy and popular model for galaxy lenses is the singular isothermal sphere with a three-dimensional density distribution of

where σv is the one-dimensional velocity dispersion. Projecting the matter on a plane, one obtains the circularly-symmetric surface mass distribution

With M(ξ) = ∫ ξ0 Σ(ξ′)2πξ′dξ′ plugged into Equation (4), one obtains the deflection angle for an isothermal sphere, which is a constant (i.e. independent of the impact parameter ξ):

In “practical units” for the velocity dispersion this can be expressed as:

Two generalizations of this isothermal model are commonly used: Models with finite cores are more realistic for (spiral) galaxies. In this case the deflection angle is modified to (core radius ξc):

Furthermore, a realistic galaxy lens usually is not perfectly symmetric but is slightly elliptical. Depending on whether one wants an elliptical mass distribution or an elliptical potential, various formalisms have been suggested. Detailed treatments of elliptical lenses can be found in [14, 24, 89, 93, 104, 172].

3.6 Lens mapping

In the vicinity of an arbitrary point, the lens mapping as shown in Equation (7) can be described by its Jacobian matrix \({\mathcal A}\):

Here we made use of the fact (see [27, 166]), that the deflection angle can be expressed as the gradient of an effective two-dimensional scalar potential ψ: ⃗∇θψ = ⃗α, where

and Φ(⃗r) is the Newtonian potential of the lens.

The determinant of the Jacobian \({\mathcal A}\) is the inverse of the magnification:

Let us define

The Laplacian of the effective potential ψ is twice the convergence:

With the definitions of the components of the external shear γ,

and

(where the angle φ reflects the direction of the shear-inducing tidal force relative to the coordinate system), the Jacobian matrix can be written

The magnification can now be expressed as a function of the local convergence κ and the local shear γ:

Locations at which det A = 0 have formally infinite magnification. They are called critical curves in the lens plane. The corresponding locations in the source plane are the caustics. For spherically symmetric mass distributions, the critical curves are circles. For a point lens, the caustic degenerates into a point. For elliptical lenses or spherically symmetric lenses plus external shear, the caustics can consist of cusps and folds. In Figure 4 the caustics and critical curves for an elliptical lens with a finite core are displayed.

The critical curves (upper panel) and caustics (lower panel) for an elliptical lens. The numbers in the right panels identify regions in the source plane that correspond to 1, 3 or 5 images, respectively. The smooth lines in the right hand panel are called fold caustics; the tips at which in the inner curve two fold caustics connect are called cusp caustics.

3.7 Time delay and “Fermat’s” theorem

The deflection angle is the gradient of an effective lensing potential ψ (as was first shown by [166]; see also [27]). Hence the lens equation can be rewritten as

or

The term in brackets appears as well in the physical time delay function for gravitationally lensed images:

This time delay surface is a function of the image geometry (⃗θ, ⃗β), the gravitational potential ψ, and the distances DL, DS, and DLS. The first part — the geometrical time delay τgeom — reflects the extra path length compared to the direct line between observer and source. The second part — the gravitational time delay τgrav — is the retardation due to gravitational potential of the lensing mass (known and confirmed as Shapiro delay in the solar system). From Equations (39, 40), it follows that the gravitationally lensed images appear at locations that correspond to extrema in the light travel time, which reflects Fermat’s principle in gravitational-lensing optics.

The (angular-diameter) distances that appear in Equation (40) depend on the value of the Hubble constant [202]; therefore, it is possible to determine the latter by measuring the time delay between different images and using a good model for the effective gravitational potential ψ of the lens (see [106, 149, 205] and Section 4.1).

• Going further. This section followed heavily the elegant presentation of the basics of lensing in Narayan and Bartelmann [128]. Many more details can be found there. More complete derivations of the lensing properties are also provided in all the introductory texts mentioned in Section 1, in particular in [169].

More on the formulation of gravitational lens theory in terms of time-delay and Fermat’s principle can be found in Blandford and Narayan [27] and Schneider [166]. Discussions of the concept of “distance” in relation to cosmology/curved space can be found in Section 3.5 of [169] or Section 14.4 of [202].

4 Lensing Phenomena

In this section, we describe different groups of gravitational lens observations. The subdivision is pragmatic rather than entirely logical. It is done partly by lensed object, or by lensing object, or by lensing strength. The ordering roughly reflects the chronological appearance of different sub-disciplines to lensing. The following sections are on:

-

Multiply-imaged quasars.

-

Quasar microlensing.

-

Einstein rings.

-

Giant luminous arcs and arclets.

-

Weak lensing / Statistical lensing.

-

Cosmological aspects of (strong) lensing.

-

Galactic microlensing.

Comprehensive reviews could be written on each separate subject. Hence the treatment here can be only very cursory.

4.1 Multiply-imaged quasars

In 1979, gravitational lensing became an observational science when the double quasar Q0957+561 was discovered. This was the first example of a lensed object [194]. The discovery itself happened rather by accident; the discoverer Dennis Walsh describes in a nice account how this branch of astrophysics came into being [193].

It was not entirely clear at the beginning, though, whether the two quasar images really were an illusion provided by curved space-time — or rather physical twins. But intensive observations soon confirmed the almost identical spectra. The intervening “lensing” galaxy was found, and the “supporting” cluster was identified as well. Later very similar lightcurves of the two images (modulo offsets in time and magnitude) confirmed this system beyond any doubt as a bona fide gravitational lens.

By now about two dozen multiply-imaged quasar systems have been found, plus another ten good candidates (updated tables of multiply-imaged quasars and gravitational lens candidates are provided, e.g., by the CASTLE group [57]).

This is not really an exceedingly large number, considering a 20 year effort to find lensed quasars. The reasons for this “modest” success rate are:

-

1.

Quasars are rare and not easy to find (by now roughly 104 are known).

-

2.

The fraction of quasars that are lensed is small (less than one percent).

-

3.

It is not trivial at all to identify the lensed (i.e. multiply-imaged) quasars among the known ones.

Gravitationally lensed quasars come in a variety of classes: double, triple and quadruple systems; symmetric and asymmetric image configurations are known.

For an overview of the geometry of multiply-imaged quasar systems, see the collection of images found at [71].

A recurring problem connected with double quasars is the question whether they are two images of a single source or rather a physical association of two objects (with three or more images it is more and more likely that it is lensed system). Few systems are as well established as the double quasar Q0957+561; but many are considered “safe” lenses as well. Criteria for “fair”, “good”, or “excellent” lensed quasar candidates comprise the following:

-

There are two or more point-like images of very similar optical color.

-

Redshifts (or distances) of both quasar images are identical or very similar.

-

Spectra of the various images are identical or very similar to each other.

-

There is a lens (most likely a galaxy) found between the images, with a measured redshift much smaller than the quasar redshift (for a textbook example see Figure 5).

-

If the quasar is intrinsically variable, the fluxes measured from the two (or more) images follow a very similar light curve, except for certain lags — the time delays — and an overall offset in brightness (cf. Figure 8).

A recent example for the identification of the lensing galaxy in a double quasar system [44]: The left panel shows on infrared (J-band) observation of the two images of double quasar HE 1104–1825 (zQ = 2.316, Δθ = 3.2 arcsec). The right panel obtained with some new deconvolution technique nicely reveals the lensing galaxy (at zG = 1.66) between the quasar images. (Credits: European Southern Observatory [182].)

Optical Lightcurves of images Q0957+561 A and B (top panel: g-band; bottom panel: r-band). The blue curve is the one of leading image A, the red one the trailing image B. Note the steep drop that occured in December 1994 in image A and was seen in February 1996 in image B. The light curves are shifted in time by about 417 days relative to each other. (Credits: Tomislav Kundić; see also [106])

For most of the known multiple quasar systems, only some of the above criteria are fully confirmed. And there are also good reasons not to require perfect agreement with this list. For example, the lensing galaxy could be superposed to one quasar image and make the quasar appear extended; color/spectra could be affected by dust absorption in the lensing galaxy and appear not identical; the lens could be too faint to be detectable (or even a real dark lens?); the quasar could be variable on time scales shorter than the time delay; microlensing can affect the lightcurves of the images differently. Hence, it is not easy to say how many gravitationally lensed quasar systems exist. The answer depends on the amount of certainty one requires. In a recent compilation, Keeton and Kochanek [92] put together 29 quasars as lenses or lens candidates in three probability “classes”.

Gravitationally lensed quasar systems are studied individually in great detail to get a better understanding of both lens and source (so that, e.g., a measurement of the time delay can be used to determine the Hubble constant). As an ensemble, the lens systems are also analysed statistically in order to get information about the population of lenses (and quasars) in the universe, their distribution in distance (i.e. cosmic time) and mass, and hence about the cosmological model (more about that in Section 4.6). Here we will have a close look on one particularly well investigated system.

4.1.1 The first lens: Double quasar Q0957+561

The quasar Q0957+561 was originally found in a radio survey, subsequently an optical counterpart was identified as well. After the confirmation of its lens nature [194, 193], this quasar attracted quite some attention. Q0957+561 has been looked at in all available wavebands, from X-rays to radio frequencies. More than 100 scientific papers have appeared on Q0957+561 (cf. [142]), many more than on any other gravitational lens system. Here we will summarize what is known about this system from optical and radio observations.

In the optical light, Q0957+561 appears as two point images of roughly 17 mag (R band) separated by 6.1 arcseconds (see Figure 6). The spectra of the two quasars reveal both redshifts to be zQ = 1.41. Between the two images, not quite on the connecting line, the lensing galaxy (with redshift zG = 0.36) appears as a fuzzy patch close to the component B. This galaxy is part of a cluster of galaxies at about the same redshift. This is the reason for the relatively large separation for a galaxy-type lens (typical galaxies with masses of 1011–12M⊙ produce splitting angles of only about one arcsecond, see Equation (10)). In this lens system, the mass in the galaxy cluster helps to increase the deflection angles to this large separation.

In this false color Hubble Space Telescope image of the double quasar Q0957+561A,B. The two images A (bottom) and B (top) are separated by 6.1 arcseconds. Image B is about 1 arcsecond away from the core of the galaxy, and hence seen “through” the halo of the galaxy. (Credits: E.E. Falco et al. (CASTLE collaboration [57]) and NASA.)

A recent image of Q0957+561 taken with the MERLIN radio telescope is shown in Figure 7. The positions of the two point-like objects in this radio observation coincide with the optical sources. There is no radio emission detected at the position of the galaxy center, i.e. the lensing galaxy is radio-quiet. But this also tells us that a possible third image of the quasar must be very faint, below the detection limit of all the radio observationsFootnote 6. In Figure 7, a “jet” can be seen emerging from image A (at the top). It is not unusual for radio quasars to have such a “jet” feature. This is most likely matter that is ejected from the central engine of the quasar with very high speed along the polar axis of the central black hole. The reason that this jet is seen only around one image is that it lies outside the caustic region in the source plane, which marks the part that is multiply imaged. Only the compact core of the quasar lies inside the caustic and is doubly imaged.

As stated above, a virtual “proof” of a gravitational lens system is a measurement of the “time delay” Δt, the relative shift of the light curves of the two or more images, IA(t) and IB(t), so that IB(t) = const × IA(t + Δt). Any intrinsic fluctuation of the quasar shows up in both images, in general with an overall offset in apparent magnitude and an offset in time.

Q0957+561 is the first lens system in which the time delay was firmly established. After a decade long attempt and various groups claiming either of two favorable values [139, 146, 163, 192], Kundić et al. [106] confirmed the shorter of the two (cf. Figure 8; see also Oscoz et al. [103] and Schild & Thomson [164]):

With a model of the lens system, the time delay can be used to determine the Hubble constantFootnote 7. In Q0957+561, the lensing action is done by an individual galaxy plus an associated galaxy cluster (to which the galaxy belongs). This provides some additional problems, a degeneracy in the determination of the Hubble constant [66]. The appearance of the double quasar system including the time delay could be identical for different partitions of the matter between galaxy and cluster, but the derived value of the Hubble constant could be quite different. However, this degeneracy can be “broken”, once the focussing contribution of the galaxy cluster can be determined independently. And the latter has been attempted recently [59]. The resulting value for the Hubble constant [106] obtained by employing a detailed lens model by Grogin and Narayan [73] and the measured velocity dispersion of the lensing galaxy [58] is

where the uncertainty comprises the 95% confidence level.

• Going further. In addition to the above mentioned CASTLES list of multiple quasars with detailed information on observations, models and references [57], a similar compilation of lens candidates subdivided into “presently accepted” and “additional proposed” multiply imaged objects can be found at [71]. More time delays are becoming available for other lens systems (e.g., [23, 162]). Blandford & Kundić [26] provide a nice review in which they explore the potential to get a good determination of the extragalactic distance scale by combining measured time delays with good models; see also [161] and [205] for very recent summaries of the current situation on time delays and determination of the Hubble constant from lensing.

4.2 Quasar microlensing

Light bundles from “lensed” quasars are split by intervening galaxies. With typical separations of order one arcsecond between center of galaxy and quasar image, this means that the quasar light bundle passes through the galaxy and/or the galaxy halo. Galaxies consist at least partly of stars, and galaxy haloes consist possibly of compact objects as well.

Each of these stars (or other compact objects, like black holes, brown dwarfs, or planets) acts as a “compact lens” or “microlens” and produces at least one new image of the source. In fact, the “macro-image” consists of many “microimages” (Figure 9). But because the image splitting is proportional to the lens mass (see Equation (4)), these microimages are only of order a microarcsecond apart and can not be resolved. Various aspects of microlensing have been addressed after the first double quasar had been discovered [38, 39, 67, 90, 136, 171, 195].

“Micro-Images”: The top left panel shows an assumed “unlensed” source profile of a quasar. The other three panels illustrate the micro-image configuration as it would be produced by stellar objects in the foreground. The surface mass density of the lenses is 20% (top right), 50% (bottom left) and 80% (bottom right) of the critical density (cf. Equation (16)).

The surface mass density in front of a multiply imaged quasar is of order the “critical surface mass density”, see Equation (16). Hence microlensing should be occuring basically all the time. This can be visualized in the following way. If one assigns each microlens a little disk with radius equal to the Einstein ring, then the fraction of sky which is covered by these disks corresponds to the surface mass density in units of the critical density; this fraction is sometimes also called the “optical depth”.

The microlenses produce a complicated two-dimensional magnification distribution in the source plane. It consists of many caustics, locations that correspond to formally infinitely high magnification.

An example for such a magnification pattern is shown in Figure 10. It is determined with the parameters of image A of the quadruple quasar Q2237+0305 (surface mass density κ = 0.36; external shear γ = 0.44). Color indicates the magnification: blue is relatively low magnification (slightly demagnified compared to mean), green is slightly magnified and red and yellow is highly magnified.

Magnification pattern in the source plane, produced by a dense field of stars in the lensing galaxy. The color reflects the magnification as a function of the quasar position: the sequence blue-green-red-yellow indicates increasing magnification. Lightcurves taken along the yellow tracks are shown in Figure 11. The microlensing parameters were chosen according to a model for image A of the quadruple quasar Q2237+0305: κ = 0.36, γ = 0.44.

Microlensing Lightcurve for the yellow tracks in Figure 10. The solid and dashed lines indicate relatively small and large quasar sizes. The time axis is in units of Einstein radii divided by unit velocity.

Due to the relative motion between observer, lens and source, the quasar changes its position relative to this arrangement of caustics, i.e. the apparent brightness of the quasar changes with time. A one-dimensional cut through such a magnification pattern, convolved with a source profile of the quasar, results in a microlensed lightcurve. Examples for microlensed lightcurves taken along the yellow tracks in Figure 10 can be seen in Figure 11 for two different quasar sizes.

In particular when the quasar track crosses a caustic (the sharp lines in Figure 10 for which the magnification formally is infinite, because the determinant of the Jacobian disappears, cf. Equation (31)), a pair of highly magnified microimages appears newly or merges and disappears (see [27). Such a microlensing event can easily be detected as a strong peak in the lightcurve of the quasar image.

In most simulations it is assumed that the relative positions of the microlenses is fixed and the lightcurves are produced only by the bulk motion between quasar, galaxy and observer. A visualization of a situation with changing microlens positions can be found in Figure 12 for three different values of the surface mass density:

-

k = 0.2 in 12a.

-

k = 0.5 in 12b.

-

k = 0.8 in 12c.

mpg-Movie (6.63 MB) Still pictures of microlensing caustics for three values of the surface mass density: a) κ = 0.2; b) κ = 0.5; c) κ = 0.8. The sequences are described and analysed quantitatively in [198](For video see appendix).

The change of caustics shapes due to the motion of individual stars which can be looked at when clicking on one of the three panels of Figure 12 produces additional fluctuations in the lightcurve [105, 198].

This change of caustics shapes due to the motion of individual stars produces additional fluctuations in the lightcurve [105, 198].

Microlens-induced fluctuations in the observed brightness of quasars contain information both about the light-emitting source (size of continuum region or broad line region of the quasar, brightness profile of quasar) and about the lensing objects (masses, density, transverse velocity). Hence from a comparison between observed and simulated quasar microlensing (or lack of it) one can draw conclusions about the density and mass scale of the microlenses. It is not trivial, though, to extract this information quantitatively. The reason is that in this regime of optical depth of order one, the magnification is not due to a single isolated microlens, but it rather is a collective effect of many stars. This means individual mass determinations are not just impossible from the detection of a single caustic-crossing microlensing event, but it does not even make sense to try do so, since these events are not produced by individual lensesFootnote 8. Mass determinations can only be done in a statistical sense, by comparing good observations (frequently sampled, high photometric accuracy) with simulations. Interpreting microlensed lightcurves of multiply-imaged quasars allows to determine the size of the continuum emitting region of the quasar and to learn even more about the central engine [69, 83, 147, 199].

So far the “best” example of a microlensed quasar is the quadruple quasar Q2237+0305 [79, 80, 110, 135, 199, 200, 207]. In Figure 13 two images of this system are shown which were taken in 1991 and 1994, respectively. Whereas on the earlier observation image B (top) is clearly the brightest, three years later image A (bottom) is at least comparable in brightness. Since the time delay in this system is only a day or shorter (because of the symmetric image arrangement), any brightness change on larger time scales must be due to microlensing. In Figure 14 lightcurves are shown for the four images of Q2237+0305 over a period of almost a decade (from [109]). The changes of the relative brightnesses of these images induced by microlensing are obvious.

4.3 Einstein rings

If a point source lies exactly behind a point lens, a ring-like image occurs. Theorists had recognized early on [40, 55] that such a symmetric lensing arrangement would result in a ring-image, a so-called “Einstein-ring”. Can we observe Einstein rings? There are two necessary requirements for their occurence: the mass distribution of the lens needs to be axially symmetric, as seen from the observer, and the source must lie exactly on top of the resulting degenerate point-like caustic. Such a geometric arrangement is highly unlikely for point-like sources. But astrophysical sources in the real universe have a finite extent, and it is enough if a part of the source covers the point caustic (or the complete astroid caustic in a case of a not quite axial-symmetric mass distribution) in order to produce such an annular image.

In 1988, the first example of an “Einstein ring” was discovered [77]. With high resolution radio observations, the extended radio source MG1131+0456 turned out to be a ring with a diameter of about 1.75 arcsec. The source was identified as a radio lobe at a redshift of zS = 1.13, whereas the lens is a galaxy at zL = 0.85. Recently, a remarkable observation of the Einstein ring 1938+666 was presented [94]. The infrared HST image shows an almost perfectly circular ring with two bright parts plus the bright central galaxy. The contours agree very well with the MERLIN radio map (see Figure 15).

Einstein ring 1938+666 (from [94]): The left panel shows the radio map as contour superimposed on the grey scale HST/NiCMOS image; the right panel is a color depiction of the infrard HST/NICMOS image. The diameter of the ring is about 0.95 arcseconds. (Credits: Neal Jackson.)

By now about a half dozen cases have been found that qualify as Einstein rings [127].

Their diameters vary between 0.33 and about 2 arcseconds. All of them are found in the radio regime, some have optical or infrared counterparts as well. Some of the Einstein rings are not really complete rings, but they are “broken” rings with one or two interruptions along the circle. The sources of most Einstein rings have both an extended and a compact component. The latter is always seen as a double image, separated by roughly the diameter of the Einstein ring. In some cases monitoring of the radio flux showed that the compact source is variable. This gives the opportunity to measure the time delay and the Hubble constant H0 in these systems.

The Einstein ring systems provide some advantages over the multiply-imaged quasar systems for the goal to determine the lens structure and/or the Hubble constant. First of all the extended image structure provides many constraints on the lens. A lens model can be much better determined than in cases of just two or three or four point-like quasar images. Einstein rings thus help us to understand the mass distribution of galaxies at moderate redshifts. For the Einstein ring MG 1654+561 it was found [100] that the radially averaged surface mass density of the lens was fitted well with a distribution like Σ(r) ∝ rα, where α lies between -1.1 ≤ α ≤ -0.9 (an isothermal sphere would have exactly α = -1!); there was also evidence found for dark matter in this lensing galaxy.

Second, since the diameters of the observed rings (or the separations of the accompanying double images) are of order one or two arcseconds, the expected time delay must be much shorter than the one in the double quasar Q0957+561 (in fact, it can be arbitrarily short, if the source happens to be very close to the point caustic). This means one does not have to wait so long to establish a time delay (but the source has to be variable intrinsically on even shorter time scales. . . ).

The third advantage is that since the emitting region of the radio flux is presumably much larger than that of the optical continuum flux, the radio lightcurves of the different images are not affected by microlensing. Hence the radio lightcurves between the images should agree with each other very well.

Another interesting application is the (non-)detection of a central image in the Einstein rings. For singular lenses, there should be no central image (the reason is the discontinuity of the deflection angle). However, many galaxy models predict a finite core in the mass distribution of a galaxy. The non-detection of the central images puts strong constraints on the size of the core radii.

4.4 Giant luminous arcs and arclets

Zwicky had pointed out the potential use in the 1930s, but nobody had really followed up the idea, not even after the discovery of the lensed quasars: Galaxies can be gravitationally lensed as well. Since galaxies are extended objects, the apparent consequences for them would be far more dramatic than for quasars: galaxies should be heavily deformed once they are strongly lensed.

It came as quite a surprise when in 1986 Lynds & Petrosian [114] and Soucail et al. [178] independently discovered this new gravitational lensing phenomenon: magnified, distorted and strongly elongated images of background galaxies which happen to lie behind foreground clusters of galaxies (recent HST images of these two original arc clusters (and others) compiled by J.-P. Kneib can be found at [96], [97].

Rich clusters of galaxies at redshifts beyond z ≈ 0.2 with masses of order 1014M⊙ are very effective lenses if they are centrally concentrated. Their Einstein radii are of the order of 20 arcseconds. Since most clusters are not really spherical mass distributions and since the alignment between lens and source is usually not perfect, no complete Einstein rings have been found around clusters. But there are many examples known with spectacularly long arcs which are curved around the cluster center, with lengths up to about 20 arcseconds.

The giant arcs can be exploited in two ways, as is typical for many lens phenomena. Firstly they provide us with strongly magnified galaxies at (very) high redshifts. These galaxies would be too faint to be detected or analysed in their unlensed state. Hence with the lensing boost we can study these galaxies in their early evolutionary stages, possibly as infant or proto-galaxies, relatively shortly after the big bang. The other practical application of the arcs is to take them as tools to study the potential and mass distribution of the lensing galaxy cluster. In the simplest model of a spherically symmetric mass distribution for the cluster, giant arcs form very close to the critical curve, which marks the Einstein ring. So with the redshifts of the cluster and the arc it is easy to determine a rough estimate of the lensing mass by just determining the radius of curvature and interpreting it as the Einstein radius of the lens system.

More detailed modelling of the lensing clusters which allows for the asymmetry of the mass distribution according to the visible galaxies plus an unknown dark matter component provides more accurate determinations for the total cluster mass and its exact distribution. More than once this detailed modelling predicted additional (counter-) images of giant arcs, which later were found and confirmed spectroscopically [99, 49].

Gravitational lensing is the third method for the determination of masses of galaxy clusters, complementary to the mass determinations by X-ray analysis and the old art of using the virial theorem and the velocity distribution of the galaxies (the latter two methods use assumptions of hydrostatic or virial equilibrium, respectively). Although there are still some discrepancies between the three methods, it appears that in relaxed galaxy clusters the agreement between these different mass determinations is very good [9].

Some general results from the analysis of giant arcs in galaxy clusters are: Clusters of galaxies are dominated by dark matter. The typical “mass-to-light ratios” for clusters obtained from strong (and weak, see below) lensing analyses are M/L ≥ 100M⊙/L⊙ [84].

The distribution of the dark matter follows roughly the distribution of the light in the galaxies, in particular in the central part of the cluster. The fact that we see such arcs shows that the central surface mass density in clusters must be high. The radii of curvature of many giant arcs is comparable to their distance to the cluster centers; this shows that core radii of clusters — the radii at which the mass profile of the cluster flattens towards the center — must be of order this distance or smaller. For stronger constraints detailed modelling of the mass distribution is required.

In Figures 16 and 17 two of the most spectacular cluster lenses producing arcs can be seen: Clusters Abell 2218 and CL0024+1654. Close inspection of the HST image of Abell 2218 reveals that the giant arcs are resolved (Figure 16), structure can be seen in the individual components [98] and used for detailed mass models of the lensing cluster. In addition to the giant arcs, more than 100 smaller “arclets” can be identified in Abell 2218. They are farther away from the lens center and hence are not magnified and curved as much as the few giant arcs. These arclets are all slightly distorted images of background galaxies. With the cluster mass model it is possible to predict the redshift distribution of these galaxies. This has been successfully done in this system with the identification of an arc as a star-forming region, opening up a whole new branch for the application of cluster lenses [50].

Galaxy Cluster Abell 2218 with Giant Luminous Arcs and many arclets, imaged with the Hubble Space Telescope. The original picture can be found in [98]. (Credits: W. Couch, R. Ellis and NASA.)

In another impressive exposure with the Hubble Space Telescope, the galaxy cluster CL0024+1654 (redshift z = 0.39) was deeply imaged in two filters [33]. The combined picture (Figure 17) shows very nicely the reddish images of cluster galaxies, the brightest of them concentrated around the center, and the bluish arcs. There are four blue images which all have a shape reminiscent of the Greek letter Θ. All the images are resolved and show similar structure (e.g., the bright fishhook-like feature at one end of the arcs), but two of them are mirror inverted, i.e. have different parity! They lie roughly on a circle around the center of the cluster and are tangentially elongated. There is also another faint blue image relatively close to the cluster center, which is extended radially. Modelling reveals that this is a five-image configuration produced by the massive galaxy cluster. All the five arcs are images of the same galaxy, which is far behind the cluster at a much higher redshift and most likely undergoes a burst of star formation. This is a spectacular example of the use of a galaxy cluster as a “Zwicky” telescope.

In CL0024+1654 the lensing effect produces a magnification of roughly a factor of ten. Combined with the angular resolution of the HST of 0.1 arcsec, this can be used to yield a resolution that effectively corresponds to 0.01 arcsec (in the tangential direction), unprecedented in direct optical imaging. Colley et al. [42] map the five images “backward” to the source plane with their model for the cluster lens and hence reconstruct the unlensed source. They get basically identical source morphology for all arcs, which confirms that the arcs are all images of one source.

Recently, yet another superlative about cluster lenses was found: A new giant luminous arc was discovered in the field of the galaxy cluster CL1358+62 with the HST [62].

This arc-image turned out to be a galaxy at a redshift of z = 4.92. Up to a few months ago this was the most distant object in the universe with a spectroscopically measured redshift! In contrast to most other arcs, this one is very red. The reason is that due to this very high redshift, the Lyman-α emission of the galaxy, which is emitted in the ultra-violet part of the electromagnetic spectrum at a wavelength of 1216 Åis shifted by a factor of z + 1 ≈ 6 to the red part at a wavelength of about 7200 Å!

4.5 Weak/statistical lensing

In contrast to the phenomena that were mentioned so far, “weak lensing” deals with effects of light deflection that cannot be measured individually, but rather in a statistical way only. As was discussed above “strong lensing” — usually defined as the regime that involves multiple images, high magnifications, and caustics in the source plane — is a rare phenomenon. Weak lensing on the other hand is much more common. In principle, weak lensing acts along each line of sight in the universe, since each photon’s path is affected by matter inhomogeneities along or near its path. It is just a matter of how accurate we can measure (cf. [144]).

Any non-uniform matter distribution between our observing point and distant light sources affects the measurable properties of the sources in two different ways: The angular size of extended objects is changed and the apparent brightness of a source is affected, as was first formulated in 1967 by Gunn [74, 75].

A weak lensing effect can be a small deformation of the shape of a cosmic object, or a small modification of its brightness, or a small change of its position. In general the latter cannot be observed, since we have no way of knowing the unaffected positionFootnote 9.

The first two effects — slight shape deformation or small change in brightness — in general cannot be determined for an individual image. Only when averaging over a whole ensemble of images it is possible to measure the shape distortion, since the weak lensing (due to mass distributions of large angular size) acts as the coherent deformation of the shapes of extended background sources.

The effect on the apparent brightness of sources shows that weak lensing can be both a blessing and a curse for astronomers: The statistical incoherent lens-induced change of the apparent brightness of (widely separated) “standard candles” — like type Ia supernovae — affects the accuracy of the determination of cosmological parameters [63, 88, 197].

The idea to use the weak distortion and tangential alignment of faint background galaxies to map the mass distribution of foreground galaxies and clusters has been floating around for a long time. The first attempts go back to the years 1978/79, when Tyson and his group tried to measure the positions and orientations of the then newly discovered faint blue galaxies, which were suspected to be at large distances. Due to the not quite adequate techniques at the time (photographic plates), these efforts ended unsuccessfully [185, 191]. Even with the advent of the new technology of CCD cameras, it was not immediately possible to detect weak lensing, since the pixel size originally was relatively large (of order an arcsecond). Only with smaller CCD pixels, improved seeing conditions at the telecope sites and improved image quality of the telescope optics the weak lensing effect could ultimately be measured.

Weak lensing is one of the two sub-disciplines within the field of gravitational lensing with the highest rate of growth in the last couple of years (along with galactic microlensing). There are a number of reasons for that:

-

1.

The availability of astronomical sites with very good seeing conditions.

-

2.

The availability of large high resolution cameras with fields of view of half a degree at the moment (aiming for more).

-

3.

The availability of methods to analyse these coherent small distortions.

-

4.

The awareness of both observers and time allocation committees about the potential of these weak lensing analyses for extragalactic research and cosmology.

Now we will briefly summarize the technique of how to use the weak lensing distortion in order to get the mass distribution of the underlying matter.

4.5.1 Cluster mass reconstruction

The first real detection of a coherent weak lensing signal of distorted background galaxies was measured in 1990 around the galaxy clusters Abell 1689 and CL1409+52 [186]. It was shown that the orientation of background galaxies — the angle of the semi-major axes of the elliptical isophotes relative to the center of the cluster — was more likely to be tangentially oriented relative to the cluster than radially. For an unaffected population of background galaxies one would expect no preferential direction. This analysis is based on the assumption that the major axes of the background galaxies are intrinsically randomly oriented.

With the elegant and powerful method developed by Kaiser and Squires [87] the weak lensing signal can be used to quantitatively reconstruct the surface mass distribution of the cluster. This method relies on the fact that the convergence κ(θ) and the two components of the shear γ1(θ), γ2(θ) are linear combinations of the second derivative of the effective lensing potential Ψ(θ) (cf. Equations (33, 34, 35)). After Fourier transforming the expressions for the convergence and the shear one obtains linear relations between the transformed components ̃κ, ̃γ1, ̃γ2. Solving for ̃κ and inverse Fourier transforming gives an estimate for the convergence κ (details can be found in [87, 86, 128] or [179]).

The original Kaiser-Squires method was improved/modified/extended/generalized by various authors subsequently. In particular the constraining fact that observational data are available only in a relatively small, finite area was implemented. Maximum likelihood techniques, non-linear reconstructions as well as methods using the amplification effect rather than the distortion effect complement each other. Various variants of the mass reconstruction technique have been successfully applied to more than a dozen rich clusters by now.

Descriptions of various techniques and applications for the cluster mass reconstruction can be found in, e.g., [1, 16, 18, 20, 30, 34, 76, 85, 129, 170, 173, 174, 176, 206]. In Figure 18 a recent example for the reconstructed mass distribution of galaxy cluster CL1358+62 is shown [78].

The reconstructed mass distribution of cluster CL1358+62 from a weak lensing analysis is shown as contour lines superposed on the image taken with the Hubble Space Telescope [78]. The map is smoothed with a Gaussian of size 24 arcsec (see shaded circle). The center of the mass distribution agrees with the central elliptical galaxy. The numbers indicate the reconstructed surface mass density in units of the critical one. (Credits: Henk Hoekstra.)

• Going further. We could present here only one weak lensing issue in some detail: the reconstruction of the mass distribution of galaxy clusters from weakly distorted background images. Many more interesting weak lensing applications are under theoretical and observational investigation, though. To name just a few:

— Constraints on the distribution of the faint galaxies from weak lensing (e.g., [61, 113]);

— galaxy-galaxy lensing (e.g., [32]);

— lensing by galaxy halos in clusters (e.g., [130]);

— weak lensing effect by large scale structure and/or detection of dark matter concentrations; this considers both shear effects as well as magnification effects (e.g. [13, 17, 168, 204]);

— determination of the power spectrum of the matter distribution (e.g. [22]); or

— the weak lensing effects on the cosmic microwave background (e.g. [119, 122, 175]).

An upcoming comprehensive review on weak lensing by Schneider & Bartelmann [21] treats both theory and applications of weak lensing in great depths.

4.6 Cosmological aspects of (strong) lensing

Gravitational lenses can be used in two different ways to study the cosmological parameters of the universe. The first is to explore a particular lens system in great detail, determine all possible observational parameters (image positions/brightnesses/shapes; matter/light distribution of lens; time variability etc.) and model both lens and source in as much detail as possible. This way one can in principle determine the amount of dark matter in the lens and -maybe even more importantly — the value of the Hubble constant. A reliable determination of the Hubble constant establishes the extragalactic distance scale, something astronomers have been trying to do for more than 70 years [126].

The second approach is of statistical nature: find out how many (what fraction of) quasars are multiply imaged by gravitationally lensing, determine their separation and redshift distributions [184] and deduce the value of (or limits to) Ωcompact — matter in clumps of, say, 106 ≤ M/M⊙ ≤ 1014 — and to ΩΛ — the value of the cosmological constant.

The first approach has already been treated in Section 4.1. Here we will concentrate on the statistical approach. In order to determine which fraction of a certain group of objects is affected by strong lensing (i.e. multiply imaged), one first needs a well-defined underlying sample. What needs to be done is the following:

-

1.

Do a systematic study of a sample of high-redshift objects: quasar surveys.

-

2.

Identify the gravitational lens systems among them.

-

3.

Determine the relative frequency of lensed objects, the distribution of splitting angles Δθ as a function of lens and source redshifts zL/zS.

-

4.

Determine matter content of universe Ωcompact, typical mass scale Mlens, cosmological constant ΩΛ, by comparison with theoretical models/simulations.

Since quasars are rare objects and lensing is a relatively rare phenomenon, steps 1 and 2 are quite difficult and time-consuming. Nevertheless, a number of systematic quasar surveys with the goal to find (many) lens systems with well defined selection criteria have been done in the past and others are underway right now (e.g. [35, 116, 118, 201, 209]).

The largest survey so far, the CLASS survey, has looked at about 7000 radio sources at the moment (the goal is 10000). In total CLASS found 12 new lens systems so far. Interestingly, all the lenses have small separations (Δθ < 3arcsec), and all lensing galaxies are detected [35, 82]. That leaves little space for a population of dark objects with masses of galaxies or beyond. A detailed discussion of lens surveys and a comparison between optical and radio surveys can be found in [101].

The idea for the determination of the cosmological constant ΩΛ = Λ/(3H 20 ) from lens statistics is based on the fact that the relative lens probability for multiple imaging increases rapidly with increasing ΩΛ (cf. Figure 9 of [37]). This was first pointed out 1990 [64, 183]. The reason is the fact that the angular diameter distances DS, DL, DLS depend strongly on the cosmological model. And the properties that determine the probability for multiple lensing (i.e. the “fractional volume” that is affected by a certain lens) depend on these distances [37]. This can be seen, e.g. when one looks at the critical surface mass density required for multiple imaging (cf. Equation (16)) which depends on the angular diameter distances.

The consequences of lensing studies on the cosmological constant can be summarized as follows. The analyses of the frequency of lensing are based on lens systems found in different optical and radio surveys. The main problem is still the small number of lenses. Depending on the exact selection criteria, only a few lens systems can be included in the analyses. Nevertheless, one can use the existing samples to put limits on the cosmological constant. Two different studies found 95%-confidence limits of ΩΛ < 0.66 [102] and ΩΛ < 0.7 [117, 156]. This is based on the assumption of a flat universe (Ωmatter + ΩΛ= 1). Investigations on the matter content of the universe from (both “macro-” and “micro-”) lensing generally conclude that the fractional matter in compact form cannot exceed a few percent of the critical density (e.g. [36, 46, 131, 167]).

4.7 Galactic microlensing

It has been known for more than two decades that halos of galaxies must contain some unknown kind of dark matter. Many different particles/objects had been suggested as constituents of this halo dark matter. The candidates can be divided into the two broad categories “elementary particles” and “astronomical bodies”. A conservative candidate for this dark matter are brown dwarfs, objects with masses less than 0.08M⊙ so that the central temperature is not high enough to start helium fusion. These objects are certain to exist, we just do not know how many there are.

In 1986 Paczyński [137] suggested a method to test observationally whether the Milky Way halo is made of such brown dwarfs (or other astronomical objects in roughly this mass range). Subsequently this type of dark matter candidate was labelled “Macho” for MAssive Compact Halo Object [72]. If one could continuously observe the brightness of stars of our neighbouring galaxy Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC) one should see typical fluctuations in some of these stars due to the fact that every now and then one of these compact halo objects passes in front of the star and magnifies its brightness. The only problem with this experiment is the low probability for such an event: Only about one out of three million LMC stars would be significantly magnified at any given time.

The underlying scenario is very simple: Due to the relative motion of observer, lensing Macho and source star the projected impact parameter between lens and source changes with time and produces a time dependent magnification. If the impact parameter is smaller than an Einstein radius then the magnification is μmin > 1.34 (cf. Equation (22)).

For an extended source such a sequence is illustrated in Figure 19 for five instants of time. The separation of the two images is of order two Einstein radii when they are of comparable magnification, which corresponds to only about a milliarcsecond. Hence the two images cannot be resolved individually, we can only observe the brightness of the combined image pair. This is illustrated in Figures 20 and 21 which show the relative tracks and the respective light curves for five values of the minimum impact parameter umin.

Five relative tracks between background star and foreground lens (indicated as the central star) parametrized by the impact parameter umin. The dashed line indicates the Einstein ring for the lens (after [137]).

Quantitatively, the total magnification μ = μ1 + μ2 of the two images (cf. Equation (22)) entirely depends on the impact parameter u(t) = r(t)/RE between the lensed star and the lensing object, measured in the lens plane (here RE is the Einstein radius of the lens, i.e. the radius at which a circular image appears for perfect alignment between source, lens and observer, cf. Figure 19, rightmost panel):

The time scale of such a “microlensing event” is defined as the time it takes the source to cross the Einstein radius:

Here v⊥ is the (relative) transverse velocity of the lens. We parameterized the time scale by “typical” numbers for the distances of lensed and lensing star and the relative transverse velocity. Note also that here we used the simple relation DLS = DS - DL (which is not valid for cosmological distances).

Note that from Equation (44) it is obvious that it is not possible to determine the mass of the lens from one individual microlensing event. The duration of an event is determined by three unknown parameters: the mass of the lens, the transverse velocity and the distances of lens and source. It is impossible to disentangle these for individual events. Only with a model for the spatial and velocity distribution of the lensing objects and comparison with “simulated microlensing events” it is possible to obtain information about the masses of the lensing objects and their density.

What seemed to be an impossible task at the time — namely determine the brightness of millions of stars on an almost nightly basis — was turned into three big observational campaigns within few years (MACHO, EROS, OGLE experiments). These groups looked at millions of stars in the LMC and towards the bulge of the Milky Way, and their first results appeared essentially simultaneously in the fall of 1993 [6, 12, 188]. In the meantime more groups have joined this effort, some of them with special emphases: e.g. on covering ongoing microlensing events (PLANET, DUO), or on extending the microlensing search to unresolved stars (“pixel lensing”) in the Andromeda galaxy (AGAPE) [45, 68], or to cover the Magellanic Clouds completely around the year (MOA). Here is a list of groups currently active in the search for microlensing signatures of compact objects in the halo of the Milky Way or elsewhere:

-

EROS (Experience de Recherche d’Objets Sombres) [10, 154, 56].

-

OGLE (Optical Gravitational Lens Experiment) [190, 187, 133].

-

AGAPE (Andromeda Galaxy and Amplified Pixels Experiment) [11, 3].

-

DUO (Disk Unseen Objects) [4].

-

GMAN (Global Microlensing Alert Network) [143].

The observations towards the Large Magellanic Cloud show that there are fewer microlensing events than one would expect if the halo of the Milky Way was made entirely of these compact objects. The latest published results from the microlensing experiments that monitor stars in the LMC indicate that the optical depths toward the LMC is about τ ≈ 3 × 10-7. The observations are consistent with 50% of the Milky Way halo made of compact objects with most likely masses of 0.5 +0.3-0.2 M⊙ [7]. But the number of observed events is still small (in this analysis eight events were used) and hence the uncertainties are large; in fact, it cannot even be excluded that none of the observed events is due to an unknown halo population [65].

The same type of experiment (searching for microlensing events) is being performed in the direction of the galactic bulge as well, the central part of the Milky Way. By now more than 200 microlensing events have been detected in this direction (for an example see Figure 22). Among them are a number of “binary lens”-events (which have a very typical signature of at least two caustic crossings, cf. Figure 23). This is about three times as many microlensing events as were expected/predicted. Several groups try to explain this “over-abundance” of events to have a new look at the stellar content and the dynamics of the bar/bulge of the Galaxy. The latest published results can be found in [8].

Observed Lightcurve of a microlensing event towards the bulge of the galaxy, event OGLE #6 [190]: The I-band magnitude is plotted as a function of time (Julian days). In the top panel, the constant V — I color of the star is shown. The maximum magnification is μ = 6.9 (or 2.1 mag), the duration of the event is 8.4 days. The star has constant brightness in the following year (Credits: Andrzej Udalski.)

Lightcurve of a binary microlensing event towards the bulge of the galaxy, event OGLE #7 [189]: The I-band the magnitude is plotted over time (Julian days). In the top panel the constant V-I-color of the star is shown. The maximum magnification is more than 2.5 mag higher than the unlensed brightness. The duration of the event is about 80 days. The two insets at the left part show a zoom of the two peaks. The star had constant brightness in the year preceding the microlensing event (1992). A model for this event finds a mass ratio of 1.02 between the two lensing stars, and a separation of 1.14 Einstein radii. (Credits: Andrzej Udalski.)

With these microlensing experiments gravitational lensing has established itself as a new tool to study the structure of the Milky Way. This type of microlensing also holds some promise for the future. It can be used, e.g. to study the frequency of binary stars. One of the most interesting possibilities is to detect planets around other stars by extending the sensitivity of the binary lenses to smaller and smaller companion masses [115, 196].

For a recent comprehensive presentation of galactic microlensing and beyond see [138]. Various aspects of microlensing in the local group are reviewed in detail. Another review article on the basics and the results of galactic microlensing can be found in [158].

5 Future Gravitational Lensing

Gravitational lensing is an exceptional field in astronomy in the sense that its occurence and many of its features — e.g. multiple images, time delays, Einstein rings, quasar microlensing, galactic microlensing, weak lensing — were predicted (long) before they were actually observed. Although “prediction” or predictability is considered one of the important criteria of modern science, many (astro-)physical phenomena are too complicated for a minute prediction (just think of the weather forecast). The reason why this worked here is that gravitational lensing is a simple geometrical concept which easily allows qualitative estimates and quantitative calculations. Extrapolating from these thoughts, it should be possible to look forward in time once again and predict future applications of gravitational lensing.

However, at any given time it requires very good intuition, some courage and maybe even a bit of ingenuity to predict qualitatively new phenomena. It does not need much of either to envision that the known lensing phenomena will become better, sharper, more. My predictions for the next decade in this sense are humble and modest:

No doubt there will soon be more determinations of accurate time delays in multiply-imaged quasar systems. If the models will get more precise as well, the value of the Hubble constant H0 determined from a number of lens systems will be accurate to a few percent or better and will probably turn out to be as reliable as H0 values obtained with any other method [205].

The frequencies, image separations, redshift distributions of multiply-imaged quasars and their lenses will become a major tool in differentiating between different cosmological models. The Sloan Digital Sky Survey, e.g., will discover a few hundred new lensed quasars with very well defined selection criteria, ideally suited for that purpose. Another angle on the cosmological model and the values of Ω and Λ offer the statistics of arcs. The number of high redshift galaxies seen as arcs depends crucially on the number of rich galaxy clusters at intermediate redshifts. And since different cosmological models predict very different formation redshifts for clusters, this promising road should be followed as well [19].

The new facilities which become available now or in the near future in the infrared/sub-mm/mm domain — like SCUBA, SIRTF, FIRST, IRAM — will open a completely new window in these wavelength ranges, with supposedly most spectacular results in the arcs and cluster lensing regime.

Quasar microlensing will provide information on the structure of the quasars and the intervening clumped matter. With the new X-ray telescope AXAF with its high spatial resolution it will become possible to obtain X-ray lightcurves which due to the presumably smaller emission region will produce dramatic microlensing events in multiply-imaged quasars. Maybe we can “map” the hot spots of quasars this way.