Abstract

The term space weather refers to conditions on the Sun and in the solar wind, magnetosphere, ionosphere, and thermosphere that can influence the performance and reliability of space-borne and ground-based technological systems and that can affect human life and health. Our modern hi-tech society has become increasingly vulnerable to disturbances from outside the Earth system, in particular to those initiated by explosive events on the Sun: Flares release flashes of radiation that can heat up the terrestrial atmosphere such that satellites are slowed down and drop into lower orbits, solar energetic particles accelerated to near-relativistic energies may endanger astronauts traveling through interplanetary space, and coronal mass ejections are gigantic clouds of ionized gas ejected into interplanetary space that after a few hours or days may hit the Earth and cause geomagnetic storms. In this review, I describe the several chains of actions originating in our parent star, the Sun, that affect Earth, with particular attention to the solar phenomena and the subsequent effects in interplanetary space.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The term space weather refers to conditions on the Sun and in the solar wind, magnetosphere, ionosphere, and thermosphere that can influence the performance and reliability of space-borne and ground-based technological systems and that can affect human life and health (definition used by the U.S. National Space Weather Plan). Of course, this definition also encompasses the generous energy supply from the Sun through its radiation that allows the existence of life on the Earth. However, this article is not meant to address this particular topic, except for the variability of radiation effects on very short time scales, e.g., in flares. Longer time scales such as decades or even centuries are covered in Living Reviews in Solar Physics by the article “The Sun and the Earth’s Climate” by Haigh (2007).

Our modern hi-tech society has become increasingly vulnerable to disturbances from outside the Earth system, in particular to those initiated by explosive events on the Sun:

-

1.

Flares release flashes of radiation covering an immense wavelength range (from radio waves to Gamma-rays) that can, e.g., heat up the terrestrial atmosphere within minutes such that satellites drop into lower orbits.

-

2.

Solar energetic particles (SEPs), accelerated to near-relativistic energies during major solar storms arrive at the Earth’s orbit within minutes and may, among other things, severely endanger astronauts traveling through interplanetary space, i.e., outside the Earth’s protective magnetosphere.

-

3.

Coronal mass ejections (CMEs), ejected into interplanetary space as gigantic clouds of ionized gas, that after a few hours or days may eventually hit the Earth and cause, among other effects, geomagnetic storms.

The economic consequences of these effects are enormous (see, e.g., Siscoe, 2000; Lanzerotti, 2001; Baker, 2004, see also further articles in the books by Song et al., 2001, and Daglis et al., 2004). That’s one reason why space weather and its predictability have recently attained major attention, not only with the involved scientists but also with the general public. Another reason is the new quality of observational data that have been obtained over the last decade from a new generation of space-based instruments. A huge fleet of spacecraft (ULYSSES, SOHO, YOKHOH, WIND, ACE, TRACE, RHESSI, Hinode, SDO) has allowed us to advance our understanding of the processes involved near the Sun, in interplanetary space, and in the near-Earth environment, and thus to renew our picture of the Sun, the heliosphere, and the solar-terrestrial relationships (see, e.g., the review by Crooker, 2000).

For setting the stage for this article, I present a series of observations of the famous “Halloween events” that occurred during several days in late October/early November 2003. All important aspects of the space weather issue are addressed here in a very impressive way. The animation in Figure 1 shows a sequence of images taken with the EIT telescope on SOHO. A few very active regions moved across the Earth-facing side of the Sun and produced several bright flares and massive eruptions. Some of them resulted in powerful CMEs (see Figure 2 and 3 which are series of coronagraph images taken by the LASCO C2 and C3 instruments on SOHO), that were pointed towards the Earth and caused major geomagnetic storms. This type of CME where the brightening occurs simultaneously all around the coronagraphs occulting disk are called halo CMEs (Howard et al., 1982).

mpg-Movie (16433.1064453 KB) Still from a movie showing A sequence of images taken with EIT on SOHO in the light of the 19.5 nm line, between October 27 and November 7, 2003. Several active regions associated with big sunspots released a series of major flares and CMEs: the “Halloween events”. The “snowstorms” following the major eruptions were caused by relativistic protons from the flare, that reached the Earth within minutes and were able to penetrate the spacecraft and instrument housings. (For video see appendix)

mpg-Movie (1088.0 KB) Still from a movie showing A sequence of white-light images taken with the coronagraph LASCO C2 on SOHO, between October 27 and 31, 2003. Several halo CMEs occurred, but they are hard to recognize because of the violent “snowstorms” from relativistic SEPs. Note the little Kreutz comet plunging into the Sun on October 28, just hours before the first major eruption. (For video see appendix)

Intense fluxes of SEPs with relativistic energies were also generated, capable enough to penetrate the skins of spacecraft and instruments and even damage some. The “snow showers” in the images of Figures 1, 2 and 3 were in fact caused by such particles. Fortunately, the CCD cameras in these telescopes recovered after some hours. When it was finally realized how high that the radiation dose from such giant events can actually be, this issue became a primary concern in manned space exploration. Adequate protective measures must be found to ensure the astronauts’ safety on their future journeys to Moon and Mars (see, e.g., Wilson et al., 2004, and references therein).

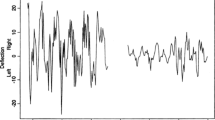

The Halloween series of X-ray flares, SEP fluxes, interplanetary magnetic field (IMF) and geomagnetic index variations is illustrated in Figure 4. The X28 flare on November 4 was in fact the strongest solar X-ray flare since the beginning of regular recordings in 1968. The X-ray sensors on the GOES satellites even went into saturation. After some proper reconstruction using calibrated proxy data the real magnitude of this flare was determined X40 which means a peak flux of 4 mW/m2 at Earth (Woods et al., 2004; Brodrick et al., 2005). Further, on October 30, two of the 12 strongest geomagnetic storms (compare Cliver and Svalgaard, 2004) since the beginning of Dst recording in 1932 occurred (−363 nT and −401 nT), with most dramatic consequences all over the globe. These storms were set loose right at those moments when the IMF turned southward (strong Bz south components).

The Halloween series (from October 28 to November 6, 2003) of X-ray flares (upper 2 panels), interplanetary magnetic field (inserted panel; the red curve is the Bz component), SEP fluxes (next 3 panels), and geomagnetic index (Kp) variations (bottom panel). The data were assembled from the NOAA webpages starting from http://www.sec.noaa.gov/today.html and the ACE page at http://sec.noaa.gov/ace/ACErtsw_home.html.

Detailed analyses of these extraordinary Halloween events and their effects were assembled in special editions of Geophysical Research Letters and Journal of Geophysical Research (see http://www.agu.org/journals/ss/VIOLCONN1/ and were reviewed by Veselovsky et al. (2004), (see also Gopalswamy et al., 2005b). These events demonstrate most impressively what space weather is about, with respect to both: its origin at the Sun, and its various effects on the Earth system.

Forecasting space weather effects is still a major challenge (Singer et al., 2001; Schwenn et al., 2005). The trustworthiness and accuracy in forecasting even the big solar events, i.e., flares and CMEs, and their impacts are still poor. They occur rather spontaneously, and we have not yet identified unique signatures that would indicate an imminent explosion and its probable onset time, location, strength, and significance for the Earth. The underlying physics is not sufficiently well understood, and thus we do not have appropriate warning tools at hands.

In this review, I will describe the several chains of actions originating in our parent star, the Sun, that affect Earth, with particular attention to the solar phenomena and the subsequent effects in interplanetary space. At first, we will inspect the solar wind itself: it is the medium in which the Earth system is imbedded and which determines the “ground state” of space weather. The solar wind interacts with the Earth’s intrinsic magnetic field and thus shapes the magnetosphere. By its variability the solar wind constantly moulds and remodels the magnetosphere. Finally, the solar wind is the medium through which disturbances from the Sun have to propagate.

Once a disturbance has reached the outer boundaries of the Earth system, a whole new series of processes will be triggered that are controlled by the Earth’s magnetic field, its ionosphere and atmosphere. Living Reviews in Solar Physics covers this issue in the article “Space Weather: Terrestrial Perspective” by Pulkkinen (2007).

2 The Solar Wind as Shaper of the Earth’s Environment

Space between the Sun and its planets is not empty as had been generally thought until the 1950s. It is filled by a tenuous magnetized plasma, which is a mixture of ions and electrons flowing away from the Sun: the solar wind. In fact, the Sun’s outer atmosphere is so hot that not even the Sun’s enormous gravity can prevent it from continually evaporating. The escaping plasma carries the solar magnetic field along, out to the border of the heliosphere where its dominance finally ends.

The solar wind (and the IMF carried with it) proves to be one key link between the solar atmosphere and the Earth system. Although the energy transferred by the solar wind is minuscule compared to both sunlight and those energies involved in Earth’s atmosphere, the solar wind is capable of pin-pricking the Earth system which eventually may react in a highly nonlinear way. There are indications of effects reaching down as far as the troposphere, and our increasingly sophisticated high-tech civilization can indeed notice them and does, at times, even suffer from them. That is why the role of the Sun and the solar wind as the drivers of space weather have gained particular attention in the recent past.

Generally, the solar wind flow is diverted around Earth by its magnetosphere that is maintained by the Earth’s intrinsic magnetic field. Solar wind particles cannot enter, unless there occurs a process called magnetic reconnection of interplanetary and planetary magnetic field lines. That may happen if the northward pointing Earth field on the front of the magnetosphere is hit by solar wind carrying a southward pointing interplanetary field. In such case, significant geomagnetic disturbances of various kinds are initiated (see, e.g., Tsurutani et al., 1988). Note that usually the IMF near the Earth does not have northward or southward pointing components. It is the intention of this section to describe the various effects by which the IMF can be tilted such that major Bz south excursions actually do occur.

The status of knowledge on the solar wind before 1972 had been very well summarized in the textbook by Hundhausen (1972). Then, from the mid 1970s on, a new class of space missions (Skylab, Helios, Voyager, and Ulysses) equipped with a new generation of instruments had initiated a new epoch in solar and heliospheric research. Numerous important discoveries were made and are documented in the literature. Major reviews can be found, e.g., in Zirker (1977); Schwenn and Marsch (1990, 1991); Kohl and Cranmer (1999); Srivastava and Schwenn (2000); Balogh et al. (2001). A comparable step forward occurred in the mid 1990s when the Yohkoh, SOHO, WIND, ACE, and TRACE spacecraft went into operation. Reviews can readily be found, e.g., in the series of SOHO Workshop Proceedings published in the ESA SP series. I further recommend the reviews in Living Reviews in Solar Physics “Kinetic Physics of the Solar Corona and Solar Wind” by Marsch (2006) and “The Solar Wind as a Turbulence Laboratory” by Bruno and Carbone (2005) and the article by Marsch et al. (2003).

2.1 The solar wind as a two-state phenomenon

From eclipse observations it has been well known that the solar corona is highly structured and dynamic (Figure 5). It changes its shape enormously during the solar activity cycle. Hence, it was no great surprise when both these properties (spatial structure and temporal variability) were found to be reproduced in the corona’s offspring, i.e., the solar wind.

Eclipse image of August 11, 1999, combined with a simultaneously taken coronagraph image (LASCO C2 on SOHO). For both images, the contrast was artificially enhanced in order to reveal the large-scale coronal structures and their sources in the lower corona (color print courtesy of S. Koutchmy, description in Koutchmy et al., 2004).

It was not until the Skylab era in 1973/74 when so-called coronal holes were discovered to be the sources of long-lived solar wind high-speed streams (Krieger et al., 1973). Coronal holes are usually located above inactive parts of the Sun, where “open” magnetic field lines prevail, e.g., at the polar caps around activity minima. In contrast, the more active near-equatorial regions on the Sun are most often associated with closed magnetic structures, such as bipolar loop systems and helmet streamers on top. From here, the more turbulent slow solar wind emerges. The embedded density fluctuations allow visualization of this type of solar wind. The images of Figure 6 (taken with the most sensible coronagraph LASCO C3 on SOHO) reveal that it is ejected continually near the equatorial plane, with the appearance of cigarette smoke. Sometimes the patterns in the out-flowing clouds can be tracked like “leaves in the wind” such that Sheeley Jr et al. (1997) could even determine the speed profile. Unfortunately, the high-speed streams above the poles remain invisible, they do not have sufficiently strong density fluctuations.

mpg-Movie (12197.4570312 KB) Still from a movie showing A sequence of white-light images taken with the coronagraph LASCO C3 on SOHO, between December 22 and 28, 1996. The Sun is at its minimum of activity. The density fluctuations in the slow solar wind near the equatorial plane makes this type of solar wind visible. Note the passage of the (occulted) Sun through the milky way around Christmas time. Note further the little Kreutz comet plunging into the Sun on December 22. (For video see appendix)

It is important to note that both: the coronal holes as well as their offspring, the high-speed solar wind streams are representatives of the inactive or “quiet” Sun. Thus, the only state of the solar wind that may deserve the label “quiet” is the high-speed wind, rather than the more variable slow wind from above active regions. This perception, first described by Feldman et al. (1976) and Bame et al. (1977), caused a major paradigm change. No longer could the slow wind be considered the “quiet” or “ground state” type although it would fit much better to the famous model of a thermally driven solar wind as derived by Parker (1958).

Figure 7 exhibits the two states of the near-minimum corona in 1998 and the associated solar wind streams rather nicely. The parts of this combined image were taken almost simultaneously from the EIT and LASCO telescopes on SOHO. This figure shows the two states by their different brightness in the corona. Note also how well separated from each other they are, both in the low corona as well as in the extended corona, i.e., in the solar wind.

In fact, the existence of sharp boundaries between solar wind streams (in longitude as well as in latitude) had already been noticed by Rosenbauer et al. (1977) and Schwenn et al. (1978) on the basis of in situ measurements from the Helios solar probes that went as close as 0.3 AU to the Sun. These two basic types of quasi-steady solar wind differ markedly in their main properties and by the location and magnetic topology of their sources in the corona, thus probably in their acceleration mechanism.

The main characteristics of the two basic states as determined by Schwenn (1990) from measurements in the plane of the ecliptic are listed in Table 1.

The main differences between the two states are, apart from the speed itself, the particle densities, the mass flux, and the helium content. However, note the striking similarities in the flux densities of energy and momentum. The latter is equivalent to the ram pressure the solar wind is exerting on an obstacle like the Earth. It appears to be invariant with the flow state within 7%. The same result was found to apply for the latitudinal stream structure up to at least 30° on heliographic latitude (Bruno et al., 1986). That means that size and shape of the Earth’s magnetosphere are not affected much by the solar wind stream structure. That aspect should be kept in mind in the space weather context.

The total energy flux density which is also invariant is the sum of two main components: the kinetic energy flux and the potential energy flux (basically the work done for moving the solar wind out of the Sun’s gravitational potential). Although these components differ strongly for the two states, their sum is about the same. There is no explanation yet for these strange invariances. We suspect that a crucial key to understanding the solar wind phenomenon is hidden here.

In addition to these two basic states, the slow solar wind filling most of the heliosphere during high solar activity can be considered a third category. It emerges above active regions distributed over large parts of the Sun, far from the heliospheric current sheet, and in a highly turbulent state. It differs in some aspects from the minimum type of slow solar wind. Finally, we regard the plasma expelled from the Sun during huge coronal mass ejections as a category on its own, because of some fundamental differences to be described later.

2.2 Solar wind in three dimensions

On the basis of the discoveries in the 1970s, a three-dimensional model of the heliosphere and the stream-structured solar wind had emerged. It is most adequately visualized in terms of the ballerina model first proposed by Alfvén (1977). Figure 8 is an artist’s view of the inner heliosphere as it may appear immediately before a typical solar activity minimum, e.g., in 1975. We find the Sun’s poles to be covered by large coronal holes. They are areas of open magnetic field lines, the northern hole being of positive (outward directed) polarity, the southern hole being negative. Some tongue-like extensions of the coronal holes reach well into the equatorial regions and give the Sun the appearance of a tilted magnetic dipole. The Sun’s equatorial region is governed by bright active centers (including some sunspots left over from the past cycle) and their loop-like and mainly closed magnetic structures above.

The “ballerina model” of the 3-D heliosphere, according to Alfvén (1977).

What looks like the skirt of a spinning ballerina is the warped separatrix between positive and negative solar magnetic field lines dragged out into interplanetary space by the radially out-flowing solar wind plasma. This separatrix carries an electric current in order to allow the magnetic polarity switch and is thus called heliospheric current sheet. It is formed on top of the closed magnetic structures at the transition between closed and open flux tubes, i.e., generally in the middle of the near-equatorial belt of activity. If the spinning skirt passes an observer sitting, say, at the Earth, he would notice a polarity switch and call it a crossing of a magnetic sector boundary. The size and number of magnetic sectors is closely related to the structure of the underlying corona. i.e., the shape of the activity belt and the coronal holes, respectively. The field lines are curved like Archimedean spirals: they denote the locations of radially flowing plasma parcels that have been released from the same source on the rotating Sun at different times (in honor of their discoverer, these spirals are called Parker spirals, see Hundhausen, 1972). Since the spiral angle (∼ 45° at 1 AU on average) depends on the flow speed, streams of different speed from contiguous sources begin interacting with each other on their way out into the heliosphere. Note though that the spiral winding does not concern the meridional component of the IMF.

The large polar coronal holes are the sources of high-speed solar wind. The emission of slow solar wind is sharply confined to a belt of about 30° width in latitude centered at the warped current sheet. The warps of both the current sheet (which can be taken to be the heliomagnetic equator, Schulz, 1973) and the coronal hole boundaries with respect to the heliographic equator allow some high-speed streams to extend to low latitudes so that they become observable at times even in the plane of the ecliptic. This occurs preferentially in the 2 years before activity minimum, when the large-scale coronal structure is rather stable, and high-speed streams reappear at the same heliographic longitudes for many solar rotations.

At times of minimum solar activity there are almost no warps left in the current sheet which is then plane like a disk lying very close to the plane of the heliographic equator. This is demonstrated in Figure 9 (from Schwenn et al., 1997) where two images registered by the LASCO coronagraphs on board SOHO in early 1996 were merged. They give a very typical example of the appearance of the extended corona at activity minimum. The inner part was taken in the light of the green coronal emission line at 530.3 nm produced by Fe xiv ions at temperatures of 2 × 106 K. This spectral line is particularly well-suited to outline hot magnetic structures in the inner corona. The outer part taken in white light shows the larger-scale electron density distribution.

A coronagraph view of the extended minimum corona on February 1, 1996. It is composed from an image taken by the LASCO C1 coronagraph onboard SOHO in the light of the green coronal emission line at 530.3 nm (inner part) and a white-light image taken by the LASCO C2 coronagraph (outer part). From Schwenn et al. (1997).

The large-scale warps of the heliospheric current sheet are caused by localized quadrupole terms of the solar magnetic field. These give rise to similar warps in the coronal hole and stream boundaries and allow them to reach at times across the heliographic equator. Thus, the stream boundaries become effective with respect to longitude. Because of the speed difference, the flows on either side begin interacting with each other with increasing distance from the Sun. In case of stable conditions, these structures appear to corotate with the Sun and are thus called corotating interaction regions (CIRs).

Figure 10 (from Schwenn, 1990) shows an idealized view of such a CIR and its evolution out to a distance of approximately 1 AU. At the Sun, the stream interface was found to be very abrupt, which is indicated in Figure 11 by the rectangular speed increase. With increasing distance, the faster plasma stream lines, having a smaller Parker angle, start pressing the slow plasma with the more strongly curved field lines. Compression and deflection of the plasma on both sides of the interface finally yield the typical profiles found at 1 AU. The total range filled with plasma affected by these interactions amounts to roughly 30° at 1 AU. However, the plasma packed into that range stems from coronal source regions originally spanning some 70° in longitude. Thus, magnetic sector boundaries are often found close to the stream interfaces at 1 AU and well within the compression regions. Note though that they usually start off at the Sun with considerable separation that often exceeds 30° (Schwenn, 1990). As a matter of fact, sector boundaries and stream interfaces have basically nothing to do with each other. Their often-observed proximity at 1 AU should be regarded as fortuitous.

An idealized view of a corotating interaction region (CIR) and its evolution from a rectangular speed profile at the Sun into a more gradual speed increase at 1 AU. From Schwenn (1990).

The “high-intensity long-duration continuous AE activity (HILDCAA) event” of May 23 to 28, 1979, and the related Alfvén wave train within the high-speed solar wind stream. The excursions of the geomagnetic AE-index follow the Bz excursions in very much detail, with a time delay of about 100 minutes. Note that within the compression region in front of the stream the Bz component is also negative, and AE reacts similarly. The global Dst index is not affected. From Tsurutani and Gonzalez (1987).

Compression and deflection of the solar wind flow in CIRs has an important consequence for the magnetic field: it undergoes the same compression and participates in the deflection process. Thus, there may arise enhanced out-of-ecliptic field components, particularly in the vicinity of magnetic sector boundaries. Here we have identified one mechanism for generating a southward pointing IMF, which is known to drive geomagnetic disturbances at Earth.

At the backside of fast streams, no interaction of the flows occurs and no CIRs develop, since here the different Parker angles lead to a separation of the flows rather than compression. The transition from the fast to the slow state is found to extend over some 60° at 1 AU. However, the location of the original stream boundary can be identified from the abrupt change in the element abundance and the ionization state (Geiss et al., 1995). Further, mapping back the flow to the Sun assuming a strictly radial flow at the locally measured speed, the original rectangular profile at the Sun is nicely reconstructed.

With increasing distance from the Sun, the compression waves at the CIRs steepen to finally form corotating shock waves (see Gosling et al., 1976). There are fast forward shocks at the front side (propagating into the slow-wind side) and fast reverse shocks traveling seemingly backward (propagating into the fast wind coming from behind). The formation of CIR shocks contributes to further eroding the originally steep stream profiles.

Corotating shocks at CIRs, in a manner similar to that of transient-related interplanetary shock waves and planetary bow shocks, can accelerate ionized particles to considerable non-thermal energies (see, e.g. Scholer et al., 1999). At times near activity minimum CIRs could be identified in plasma measurements by Ulysses (at 4 AU) at latitudes up to some 40°. At higher latitude, there was nothing but high-speed wind encountered. However, energetic particles apparently associated with CIR shocks have been observed at much higher latitudes (McKibben et al., 1995), to which the CIR shocks do not propagate (Gosling and Pizzo, 1999). That means that there must be a magnetic connection between these high latitudes and those lower latitudes where particles energized at CIRs can be injected. It may be the combined effect of differential rotation of the photosphere, rigid rotation of the corona at the equatorial rate, and the offset between the Sun’s rotational and magnetic axes that allows near-equatorial field lines to connect to high solar magnetic latitude regions (Fisk, 1996, see also Posner et al., 2001). This mechanism transfers information on the corotating stream structure to latitudes where the stream structure itself is not discernible.

A second such mechanism results from meridional “squeezing” of compression regions, as had been observed by Burlaga (1983). He concluded that compression regions may extend over larger latitudinal ranges than the high-speed streams causing them. Of course, such squeezing would imply meridional flows (Siscoe and Finley, 1969) and magnetic field excursions within these regions. This is a second mechanism for generating Bz south of the IMF. Without knowing this effect, an observer of geomagnetism at the Earth might be surprised by the sudden appearance of southward Bz completely “out of the blue.”

2.3 Solar wind and space weather

In the previous Section 2.2, I have already explained why the IMF that usually does not have major meridional components, may undergo substantial deflections leading to geoeffective Bz components that allow magnetic reconnection between the IMF and the Earth’s intrinsic field.

The action of potential reconnection is further enhanced by the pressure pulse from the compressed plasma. Rosenberg and Coleman Jr (1980) studied the behavior of Bz around sector boundaries extensively and explained it in terms of the ballerina model (see Figure 8): At a sector boundary the current sheet must necessarily be inclined versus the ecliptic plane, implying the existence of non-zero Bz components. At the transitions from well within one sector (with Bz = 0) to well within the other sector (again with Bz = 0) the observer will see a Bz < 0 first and, after crossing the stream interface, Bz > 0. This applies for any sector crossing, positive to negative and vice versa, as long as the general dipole of the Sun maintains its orientation. Once the Sun’s dipole is reverted (around solar activity maximum), the sequence of Bz excursions is also reverted. This reversal was indeed confirmed (Rosenberg and Coleman Jr, 1980). The CIR scheme in Figure 10 illustrates that the density profile in the compression region (with its increased ram pressure) is very asymmetric with respect to the sector boundary. Thus it matters a lot on which side the Bz < 0 excursion occurs, be it on the low pressure side before the boundary or at the high pressure side behind it. This phase shift between Bz < 0 and the pressure pulse varies with the 22-year magnetic solar cycle and is superimposed on the well-known 11-year modulations. Indeed, there were some unexplained 22-year periodicities in geomagnetism reported by, e.g., Chernosky (1966) and Russell (1974).

There is another fundamentally different mechanisms causing geoeffective Bz south swings:

Solar wind high-speed streams are dominated by large-amplitude transverse Alfvénic fluctuations causing major excursions of both the proton flow and the IMF vector on time scales of minutes to hours (Belcher and Davis Jr, 1971), see also Marsch (1991) and Tu and Marsch (1995). They corotate with the Sun, often for several months. Once these high-speed streams reach the Earth, the occasional southward deflections of the IMF due to the Alfvén turbulence stir medium level geomagnetic activity (see Tsurutani and Gonzalez, 1987). Bartels (1932), had postulated “M-regions” on the Sun as sources of these geomagnetic effects. The close association between high-speed streams and M-regions had already been noted in the earliest solar wind observations from the Mariner 2 space probe in 1962 (Snyder et al., 1963, see also Schwenn, 1981). Tsurutani and Gonzalez (1987) and Tsurutani et al. (2004a) inspected the effects of high-speed streams on geomagnetism in terms of what they called “high-intensity long-duration continuous AE activity (HILDCAA) events” (Figure 11). Remember that the compression and deflection of the plasma flow in the CIRs in front of high-speed streams may also lead to geomagnetic activity (Schwenn, 1981). It does not matter whether the steepening at the CIRs has already led to the formation of corotating shocks or shock pairs at the CIRs, a process which only rarely occurs inside the Earth’s orbit (see Schwenn, 1990).

The recurrence of this particular type of geomagnetic activity every 27 days, i.e., exactly in the rhythm of solar rotation, had led Bartels (1932) to postulate the existence of M-regions on the Sun already in the 1930s. He thought they were long-lived stable regions on the Sun which emit certain particles capable of stirring geomagnetism. After all, he was strikingly right except for one aspect: these M-regions are not to be sought in active regions on the Sun, as he thought, but rather in the inactive parts: the M-regions are associated with the coronal holes representative of the inactive Sun, and the geomagnetism is stirred by the streams of high-speed plasma (with their Alfvénic fluctuations) emanating from them.

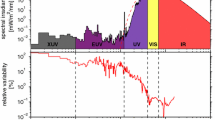

A pretty illustration of the close relation between interplanetary magnetic field, coronal holes, solar wind streams and geomagnetic effects was given by Sheeley Jr and Harvey (1981), shown in Figure 12. In the upper half, all patterns are rather regular products of the inactive Sun. Those data were from the three years before activity minimum in 1976. With the new activity rising from 1977 on, transient processes disturbed the regular stream pattern and caused sporadic strong geomagnetic storms: products of the active Sun. It is important in the context of space weather to always remember this distinction.

A 27-day Bartels display of IMF polarity, coronal hole occurrence (plus 3 days to allow for Sun-Earth transit time), solar wind speed at Earth, and geomagnetic disturbance index C9. A 27-day average sunspot number is indicated in the narrow strip on the extreme right. Coronal holes were counted only when they occurred within 400 of the solar equator. The color coding was chosen such that commonalities are best visible (for details see Sheeley Jr and Harvey, 1981).

3 Radiation from Solar Flares

Solar flares are certainly among the most dramatic and energetic fast processes in our solar system that we know of. The flashes of electromagnetic radiation released within seconds to minutes may cover a wavelength range of as much as 17 orders of magnitude: from kilometric radio waves through the infrared, visible and UV ranges down to X-rays and even Gamma-rays.

3.1 Some historical remarks

Major optical flares occur only rarely, depending on the phase of the activity cycle, and they last only a few minutes. So it was by pure luck that Mr. R.C. Carrington on September 1, 1859 at 11:18 GMT, while doing routine sunspot observations, could witness such a unique event for the first time (see the worthwhile original report by Carrington, 1860, reprinted in Meadows, 1970). The brilliancy of the flash equaled that of direct Sunlight, and at first he attributed it to a failure of his telescope. Within the 60 seconds it took him to call a witness, the flash had already much changed and enfeebled. Fortunately enough, Mr. R. Hodgson, another observer at a different location, had also seen the flash and confirmed its existence (Hodgson, 1860, also reprinted in Meadows, 1970). Carrington, in his report to the Royal Society, mentioned the potential connection of this strange solar event with the strong geomagnetic storm that occurred only 17 hours and 40 minutes later. He was honest and careful enough not to overvalue this connection (“One swallow does not make a summer.”). However, this discovery can be considered not only as a landmark in modern solar astronomy but also the beginning of space weather research.

This remarkable event was recently revisited by Tsurutani et al. (2005). They used newly reduced and calibrated ground-based magnetometer data and derived characteristic data that can be compared with those from other events in the past 145 years. It turned out that the September 1, 1859 event was among the fastest and most energetic flares ever since (Cliver and Svalgaard, 2004). Of course, there is not much information recoverable about its radiation effects, besides the visual data given by Carrington and Hodgson. But the geomagnetic effects must have been extreme. For example, aurora were sighted to geomagnetic latitudes as low as 20° (Honolulu), and fires were set by arcings from ground-induced currents (GICs) in telegraph wires, both in Europe and the U.S. (see, e.g., Tsurutani et al., 2003, 2005, and references therein).

For quite some time after the discovery of this most spectacular type of event on the Sun, various expressions have been used to name it. The solar flare nomenclature was investigated by Cliver (1995). He revealed that the term flare can be found for the first time in Bartels (1932)’s famous M-region paper. The unofficial use of this new term can be traced to a paper by Richardson (1944) who stated: “The strongest reason for the adoption of ‘flare’ is that in one word are combined the most outstanding features of the phenomenon: its sudden appearance, great brilliancy, and rapid variations in intensity.”

The flare phenomenon has always attracted the solar physics community. Thousands of flares have been observed in all detail and described in hundreds of articles and books (the interested reader is referred, e.g., to the books “Solar Flares” by Švestka, 1976 and “High Energy Solar Physics” by Ramaty et al., 1996, and to the article by Švestka, 1981, with some 500 references on flare observations, and further to the article in Living Reviews in Solar Physics “Flare Observations” by Benz, 2008). Because of their significance for solar-terrestrial relations (the term space weather has been coined not before the 1980s), flares were regularly observed by “flare patrols” at several observatories around the globe, and agencies like NOAA listed them in their Solar Geophysical Reports for many years. With the advent of regular X-ray observations from space with the SOLRAD satellite in 1968 and the GOES satellites in 1975 a new and more objective classification of flares in terms of X-ray brightness was established (for historical records see http://www.ngdc.noaa.gOv/stp/SOLAR/ftpsolarflares.html#cf).

Theoreticians and modelers have been busy in finding consistent explanations of the flare phenomenon (see, e.g., the textbook Physics of the Solar Corona by Aschwanden (2004) or the upcoming article “Physics of Solar Flares” in Living Reviews in Solar Physics). However, without going into detail here I dare to state: there is no unique, consistent, and generally accepted explanation yet.

The total energy released in the course of flares can differ by several orders of magnitude: from some 1019 J for the smallest events that are barely recognizable as “events” up to some 1025 J for the most energetic ones. Significant fractions of that energy go into radiation, the rest goes into heating and acceleration of particles, the partition depending on the type of flare.

The different kinds of radiation come from different parts of the flare site and are released at different times of the flare process. In the following sections, I will describe the various emissions organized in a timely order as they appear rather than by their spectral properties.

3.2 Soft X-rays from flares

Quite often, the first visible signature of a flare appears in soft X-rays with energies up to some tens of keV. It is thermal flare plasma radiation that signalizes the sudden heating of coronal plasma to temperatures of some 107 K. This radiation is due to the bremsstrahlung continuum and to a multitude of lines of heavily stripped ions, e.g., the line complex around 0.186 nm from helium-like iron ions. The time profiles of soft X-ray bursts are often very similar to those of simultaneous radio microwaves. Since the onset of regular observations from space in 1968, the intensity of soft X-rays has been used for flare classification. It is based on measurements (using calibrated satellite-carried instruments) of the soft X-ray emission in the 0.1 to 0.8 nm band as published in real-time by NOAA (http://www.sec.noaa.gov/today.html). For example, the big X-ray flare on October 28, 2003 was classified as X 17.2, corresponding to the measured power of 1.72 mWm−2 (see Figure 4). NOAA is presently operating its own Soft X-ray Imager (SXI) as part of their space weather service (see http://www.sec.noaa.gov/sxi/index.html). More information on presently ongoing observations of solar soft X-ray emission and flares can be found on the websites for the RHESSI mission (http://hesperia.gsfc.nasa.gov/hessi/), the Hinode mission (http://hinode.nao.ac.jp/index_e.shtml), and not to forget the excellent presentation in Wikipedia (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Solar_X-ray_astronomy).

3.3 EUV and visible light

At lower levels of the solar atmosphere, EUV emission lines allow a view on a region called flare transition layer that is also heated up quite abruptly (see example in Figure 1). From the upper chromosphere we receive the strongest signal in the Lyman-alpha line (at 121.6 nm) and the other members of the Lyman series of hydrogen. Lower down in the solar atmosphere, line emission from the Balmer series of hydrogen becomes dominant, with its most prominent member, the famous H-alpha line at 656.3 nm. In fact, most flare observations have been made using this line, since it is situated near the peak of the visible part of the solar spectrum and is thus easily accessible to ground-based observers. That is the reason why for many years the area at the time of maximum H-alpha brightness of flares and also their “importance” (faint, normal or brilliant) have been used for flare classification. Many volumes of Solar and Geophysical Data beginning in 1938 (published by NOAA) are filled with these data, and yet these lists are incomplete and suffer from non-objective judgments of different observers. A typical H-alpha flare observed from the ground is shown in Figure 13.

mpg-Movie (312.247070312 KB) Still from a movie showing The flare on June 7, 2000, 1526-1621 UT, as seen by the H-alpha telescope (HASTA) in El Leoncito, Argentina http://www.oafa.fcefn.unsj-cuim.edu.ar/hasta/. (For video see appendix)

3.4 Hard X-rays

During the flare flash phase, usually a few minutes after the soft X-ray burst, another kind of apparently non-thermal radiation (as first noted by De Jager, 1965) is observed for many but not all flares: hard X-rays with energies of tens of keV up to a few MeV in extreme cases (see, e.g. Garcia, 2004). This radiation is due to electrons accelerated to very high energies right at flare onset which then hit the atoms of the lower denser layers and produce a bremsstrahlung continuum in the form of hard X-rays.

Since 2002, the RHESSI mission (Ramaty and Mandzhavidze, 2000; Lin et al., 2003; Hurford et al., 2003), provides high-resolution imaging and spectroscopy from soft X-rays to Gamma-rays. New results are being published in a fast pace (see the ADS for authors like Lin, Krucker, Hudson, Hurford and others).

3.5 Impulsive microwave bursts

Simultaneously, this same electron population, in conjunction with strong chromospheric magnetic fields, produces gyro-synchrotron radiation that can be observed from the ground using radiotelescopes (see, e.g. Pick et al., 1990). There is a very good time correlation between the hard X-ray bursts and impulsive microwave radiation, in particular for the higher frequencies beyond 1 GHz. The spectrum is a broadband continuum with peak intensities at some tens of GHz for the strongest events. For detailed information see, e.g., Benka and Holman (1992) and Holman (2003).

Recently, a new kind of rapid solar spikes (100–500 ms) was observed at submillimetric waves (212 and 405 GHz) by the new Solar Submm-wave Telescope (SST) by Kaufmann et al. (2003). They suggest that these pulse bursts might be representative of an important early signature of CMEs, but a consistent explanation is still lacking. During the November 4, 2003 flare, a further new microwave burst spectral component was observed by Kaufmann et al. (2004), that apparently peaks in the THz to infrared range. The origin of these bursts is still unclear. This type of radio bursts might be common to many solar events, but observing them requires new techniques that are able to bridge the gap between electronics and photonics.

3.6 Type IV radio bursts

Some of these impulsive high-frequency microwave bursts are accompanied by long-lived radio enhancements at lower frequencies. Such type IV radio bursts cover a continuous spectrum with frequencies below 200 MHz, i.e., in the meter wavelength range. Sometimes their sources are seen to move away from the Sun. These moving type IV bursts were thought to be caused by electrons trapped in a closed magnetic cloud ejected from the flare site, but this interpretation is still under debate. For more information see, e.g., Švestka (1981) or Kahler (1992).

3.7 Gamma-rays (and white light)

Protons are also accelerated during the flare process. They can penetrate deeply into the solar atmosphere, into layers which are usually not involved with the flare. These protons can excite both: white light emission and Gamma-rays. Proton energies exceeding some 20 keV are required. This explains why only the really big flares are visible in white light (remember Carrington’s observation in 1859) and Gamma-rays.

There are at least six different physical processes that contribute to Gamma-ray emission: 1) electron bremsstrahlung continuum emission, 2) nuclear de-excitation line emission, 3) neutron capture line emission, 4) positron-electron annihilation line emission at 0.511 MeV, 5) pion-decay radiation at > 50 MeV (pions may be generated whenever protons are accelerated into the 1 GeV energy range), and 6) neutron production. The strongest lines in the Gamma-ray spectrum of flares are the positron-electron annihilation line at 511 keV and the 2.223 MeV line produced when neutrons are captured by protons (see, e.g., Ramaty et al., 2002; Lin et al., 2003 and Figure 14). Note that both the positrons and the neutrons must first be produced in the flare process itself. The hardest Gamma line detected so far is the 6.129 MeV line due to 16O nuclei de-excitation. The electron bremsstrahlung continuum was found with energies up to some GeV (Kanbach et al., 1993). It consists of two types: from electrons directly accelerated in the flare and from secondary electrons and positrons released in high-energy reactions (involving pion decay and muon production). For further details see, e.g., Rieger and Rank (2001).

RHESSI Gamma-ray count spectrum from 0.3 to 10 MeV, integrated over the interval 0027:20–0043:20 UT. The lines show the different components of the model used to fit the spectrum. From Lin et al. (2003).

3.8 Type III radio bursts

Major fractions of the flare-accelerated electrons and protons escape into space (to be discussed in more detail in the next Section 3.9), guided by the magnetic field lines that are carried out into the heliosphere by the evolving solar wind. Injections of electrons in the keV energy range are accompanied by radio wave emission with frequencies from MHz down to few kHz. These so-called type III radio bursts (Wild, 1950) are generated in a two-step process (see also Figure 15 from Gurnett et al, 1980): 1. electrons accelerated in solar flares to energies of some keV are streaming away from the Sun and excite plasma oscillations locally, all the way from the corona into the distant heliosphere, the frequency fp being determined by the local electron density ne:

with fp in kHz and ne in cm−3. 2. These plasma oscillations (sometimes also called Langmuir waves) are converted to escaping electromagnetic radiation (of the same frequency or its harmonic) by non-linear wave-wave interactions. The resulting radio waves can be picked up by appropriate receivers in space. Because of the outward travel of the electrons through the radial density gradient the wave frequency gradually decreases with time, and their onset times are gradually delayed. That leads to the characteristic frequency variation of type III bursts as shown in Figure 16 from Kellogg (1980). In many cases, there is an overlaid strong and more spiky signal at very low frequencies observed. It is caused by the plasma oscillations excited locally upon arrival of the electrons at the position of the observing spacecraft. In the case shown in Figure 16, the local plasma density of 7.5 cm−3 would correspond to a local plasma frequency of 24.6 kHz, which is indeed at the intensity maximum of the observed plasma oscillation spectrum. Note that the onset times of the oscillations and the waves are almost identical.

A representative radial profile of the electron plasma frequency in the solar wind illustrating the generation of electron plasma oscillations and the subsequent electromagnetic radiation at the plasmafrequency and its harmonic. From Gurnett et al. (1980).

Signal amplitude for a number of radio wave channels during the type III radio burst on December 7, 1977, as observed from Helios 2. From Kellogg (1980).

Modern antenna systems onboard spaceprobes allow determination of the direction of the source of the type III radiation. The frequency itself is a measure of the source’s plasma density which, in conjunction with an assumed density model, is a measure of the radial distance of the source. This way, the location of any particular radio source along the path of the type III electrons can be determined. Indeed, the actual shape of the Parker spiral along which these electrons have to move could be experimentally verified (Reiner et al., 1995). Simultaneous radio measurements from two distant spacecraft allow rather precise triangulation of the radiation sources and a stereoscopic view of the electron beam path, even without any assumption of a density profile (Baumback et al., 1976; Gurnett et al., 1978).

The type III electrons have a rather wide energy spectrum. Thus, their travel times to an in situ observer located at some distance from the Sun will vary considerably. That is indeed observed, as is shown in the bottom panel of Figure 17 (from Lin, 2005): the 27 keV electrons arrive about 20 minutes later than the 517 keV electrons.

Example of a flare hard X-ray burst observed by RHESSI with corresponding solar type III radio burst and energetic electrons (and Langmuir waves) observed in situ by the WIND spacecraft (Krucker and Lin, 2002). Top panel: GOES soft X-rays; second panel: Spectrogram of RHESSI X-rays from 3 to 250 keV; third and fourth panels: radio emission observed by the WIND WAVES instrument; fifth panel: Electrons from ∼ 20 to ∼400 keV observed by WIND 3-DP instrument. From Lin (2005).

3.9 Metric type II radio bursts

Many strong flares are accompanied by so-called type II radio bursts (for an early review see Nelson and Melrose, 1985). They appear as stripes of enhanced radio emission slowly drifting from high to low frequencies in dynamic radio spectra. The frequency of this characteristic radiation drops from several hundred MHz to about 20 MHz or even less within some tens of minutes. The equivalent wavelength of this radiation is in the meter range, and thus these bursts are often called metric type II radio bursts. An impressive example from Cane and Erickson (2005) is shown in Figure 18. In this particular case the first harmonic was also observed, as is often the case. It is generally thought that type II radio bursts are due to electrons accelerated at an outward propagating coronal shock front. The decrease in frequency corresponds to motion of the shock through the radial plasma density profile. For a known (or assumed) density profile, one can deduce the propagation speed of the driving shock wave.

The radio type II burst of November 1, 2003, from 22:00 UT on. This is a clear example of a strong metric type II burst that extends from 300 to 10 MHz. It was observed from 3 independent instruments: from the WAVES instrument on the WIND spacecraft and the ground-based helio-spectrogtraphs. The WAVES data cover the frequency range below 14 MHz, the BIRS data run from 14 to 57 MHz, and the Culgoora data run from 57 to 570 MHz. Fundamental and harmonic bands of the type II are easily seen, along with splitting of each band. After the type II bands, some broadband type IV is seen in the Culgoora and BIRS data. A short, type II like feature is seen in the BIRS data between 23:06 and 23:14 UT. The light area in the BIRS data between 22:34 and 22:48 UT results from ionospheric absorption of the galactic background due to solar UV. From Cane and Erickson (2005).

Sometimes the main trace of the radio-signature in the frequency-time plot is accompanied by a second component from apparently much faster propagating features. It appears as rapidly drifting (some 10 MHz/s) stripes of enhanced radio emission shooting up from the “backbone” (i.e., the main type II trace in the frequency-time plot) towards both high and low frequencies (see Figure 19 from Mann and Klassen, 2005). These “herringbones,” as Roberts (1959) called them, are regarded as signatures of upward and downward pointed electron beams, which are accelerated by the shock waves associated with the “backbone”. Mann and Klassen (2002) found some morphological differences between these herringbone electrons and the type III electrons: the latter ones are faster by about a factor of 2 and apparently result from a different acceleration process near the flare site.

Dynamic radio spectrum (A) of the solar type II burst during the event on June 30, 1995. The “backbone” is slowly drifting from 60 to 42 MHz. The “herringbones” are nicely visible during the whole event. The radio intensity is coded by grey scale. The bottom frames (B, C) present the intensity time derivative of the individual “herringbones.” From Mann and Klassen (2005).

3.10 Kilometric type II radio bursts

There is another type of solar radio bursts, called the kilometric type II radio bursts. They also drift in frequency, from a few 100 kHz to some tens of kHz over time scales of several days. Cane (1985) had established that the kilometric radio bursts are due to electrons accelerated at interplanetary shock waves on their way from the Sun out into space. In that respect, these kilometric radio burst are similar to the metric radio bursts. In some cases, the shock motion can be well traced from the Sun to the Earth orbit and often far beyond (see, e.g. Reiner et al., 1998, 2001), as is illustrated in Figure 20.

Dynamic spectra of the WIND-WAVES radio data from January 6 to 11, 1997 in the frequency range from 23 to 245 kHz. The ordinate scale is the inverse of the observing frequency. The observed type II radio emissions for this event are bracketed by the upper two lines that originate from the CME lift-off time at 15:00 UT on January 6. For a more detailed description see Reiner et al. (1998).

There is still a controversial discussion going on about the nature of the respective shocks causing the radio bursts. Cliver and some colleagues (Cliver et al., 1999, 2004; Cliver, 1999) argue that both the metric and the kilometric burst are produced by CME-driven shocks. The opposing position is held, e.g., by Cane and Reames (1988); Gopalswamy et al. (1998); Cane and Erickson (2005). They argue that the metric radio bursts stem from coronal shock waves driven by flares as blast waves, as suggested before by, e.g., Wagner and MacQueen (1983) or Sheeley Jr et al. (1984). In fact, there is never a continuous spectrum seen connecting the metric and the kilometric radio ranges. This gap had often been assigned to instrumental shortcomings. Only recently, the whole spectral range could be covered, but the gap in the spectrum usually remains. Most metric type II bursts appear to die out within 2 Rs (from Sun center) since their frequency rarely drops further than 5 MHz. This suggests that they are driven by shock waves that die out soon. On the other hand, a CME driven shock cannot be formed unless the CME speed exceeds the local fast magnetosonic speed. For a majority of the slower CMEs this stringent condition is not fulfilled before the CMEs reach a distance of several (Mann et al., 2003). That would explain why the kilometric radio bursts rarely have frequencies above 1 MHz. In some cases, both radiation types are seen simultaneously at different frequencies. That does not necessarily prove the simultaneous existence of 2 shocks. There might as well be one large shock front that manages to accelerate electrons at very different distances from the Sun.

The controversy is still open. The interested reader may wish to look up, e.g., Kahler (1992); Gopalswamy et al. (2005a); Cane and Erickson (2005); Reiner et al. (2005) and other articles by these authors and others such as Mann, Klassen, Reames, Kaiser, Webb, to be found using the NASA ADS.

3.11 Solar flares and space weather

The various types of radiation produced during the flare process are of interest in the space weather context. The EUV radiation in particular the Lyman-alpha radiation at 121.6 nm wavelength is absorbed in the Earth’s atmosphere and causes its instantaneous heating and expansion. Earth-orbiting satellites cruising in low orbits may sense a sudden drag that lowers their orbits (see Figure 5 in Lean, 1991). Any direct damage from the X-ray and Gamma radiation dose to technical systems and humans in space has not been reported, the intensities are probably too low.

The judgment of the role of flares on space weather in terms of geomagnetic effects has changed dramatically in recent years. Since Carrington’s discovery of the apparent connection between strong flares and geomagnetic activity in 1859, this connection has been considered a cause and effect relation for many years, despite some obvious shortcomings. Only in the 1980s, it became clear that the only type of solar transient that has a unique cause and effect relation to geomagnetic activity lies in CMEs, not in flares. Schwenn (1983) and Sheeley Jr et al. (1983, 1985) showed that every CME launched with a speed exceeding 400 km/s eventually drives a shock wave, which then can be observed in situ, provided that the observer is located within the angular span of that CME. If this shock and the often times following ejecta cloud hits the Earth, geomagnetic effects may occur (provided some conditions on the orientation of the interplanetary magnetic field are also fulfilled). In reverse, every shock wave observed in space (except the ones at corotating interaction regions) can uniquely be associated with an appropriately pointed CME at the Sun. This proves that there is a causal chain linking CMEs to geomagnetic effects. No similar statement can be made for flares. Indeed, there are many CMEs (with geoeffects) without associated flares, and there are flares without associated CMEs (and without geoeffects). The longstanding “flare myth” was finally abolished (see Gosling, 1993; Reames, 1999). However, for the very big and most dangerous events like the one Carrington happened to witness, strong X-ray flares and large CMEs usually occur in a close timely context (Švestka, 2001). It is now commonly thought that both: flares and CMEs, are just the symptoms of a common underlying “magnetic disease” of the Sun (Harrison, 2003).

A very different aspect in space weather issues concerns the radio bursts (not to mention here their direct effects on cell phones and the GPS system, which are addressed in the Living Reviews in Solar Physics article “Space Weather: Terrestrial Perspective” by Pulkkinen, 2007). The type III radio bursts can be tracked through large parts of the heliosphere and help to locate their probable source regions near the Sun. The curvature of the Parker spiral outlined by the type III electrons provides information on the solar wind environment through which theses electrons are passing. Even more important are the metric and kilometric type II radio bursts in that they show the motion of interplanetary shocks from the Sun up to Earth and further out. Thus, this information can be used for practical space weather analysis and forecasting.

4 Solar Energetic Particles (SEPs)

The various highly dynamic processes in the magnetized coronal and interplanetary plasma can cause major acceleration of the charged particle populations. The main locations for electron and ion acceleration are flare sites and shock waves in the corona and in interplanetary space. The energy of these solar energetic particles (SEPs) reaches from a few keV of “suprathermal particles” to some GeV. Sometimes the fastest particles obtain more than half the speed of light, and they arrive at the Earth only a few minutes after the light flash. They are of particular concern in the space weather context since they can penetrate even the skins of spaceprobes traveling outside the Earth’s magnetosphere and blind or even damage sensitive technical systems. The strongest events like the ones in August 1972 or in October/November 2003 produce radiation doses that might be lethal to unprotected astronauts while traveling in space outside our protective magnetosphere (see, e.g. Turner, 2001). For the very largest events, SEP ionization of the polar atmosphere produces nitrates that precipitate to become trapped in the Earth’s polar ice. Ice core analysis revealed that the largest SEP event in the last 400 years appears to be related to the giant flare observed by Carrington in 1859 (Reames, 2004). Forecasting such extraordinary events is still not possible, for two main reasons: 1) We have not yet identified unique signatures for the driving flare that would indicate an imminent explosion and its probable onset time, location, and strength, and 2) the size of the SEP fluxes is highly variable and appears to be only loosely related to the strength of the flare.

For illustration we show what happened during the dramatic Halloween events in late 2003. In Figure 21 (from Mewaldt et al., 2005) the SEP intensities for electrons and protons as measured by the GOES/SAMPEX/ACE satellites in several energy bands are plotted. The largest of the five major SEP events reached its peak intensity during shock passage at Earth on October 29. It had been launched in context with the X 17.2 flare and the associated halo CME about a day earlier. The maximum energy of probably more than 1 GeV was sufficient for the particles to penetrate the whole SOHO spacecraft and cause temporary malfunction of several CCD cameras (see the “snowstorms” in Figures 1, 2 and 3).

Time history of energetic protons and electrons during the period from October 26, 2003 to November 7, 2003. The top panel shows electron data from EPAM/ACE (top trace) and PET/SAMPEX (1.9 to 6.6 MeV). The SAMPEX points are averaged over separate polar passes, including only data obtained at invariant latitudes > 75°. It is possible that the intensities shown near the end of 29 October through 30 October (SEP event 3) are overestimated because of background contributions. The middle panel shows low-energy proton data from ACE/EPAM and the bottom panel includes protons measured by GOES-11 in six different energy intervals. The occurrence of X-class flares (obtained from NOAA) are indicated by dotted vertical lines with the intensity labeled above each line. Interplanetary shocks are indicated by dashed vertical lines labeled by an “s”. Major proton events during this interval are labeled 1 to 5. From Mewaldt et al. (2005).

Such big events and event sequences do not occur frequently. Since the beginning of regular registrations by NOAA in 1976 there had been only three events with slightly higher proton fluxes: on October 19, 1989 (Reeves et al., 1992), on March 24, 1991, and on November 4, 2001 (according to NOAA records, see http://goes.ngdc.noaa.gov/data/ParticleEvents.txt). Note that these three big SEP events were associated with flares of importance X13, X9, and X1, respectively, while at some much bigger flares (at similarly central positions on the Sun’s disk) the SEP fluxes remained rather low.

The acceleration of particles to such high energies on time scales of seconds or minutes as well as their propagation through space is still not well understood, and active research is going on. The interested reader may wish to study more detailed reviews than the present one can offer, e.g., Kunow et al. (1991); Reames (1999, 2001, 2002); Tylka (2001); Kahler (2001a), and of other authors such as Kallenrode, Lee, Lin, Mason.

4.1 SEPs: protons and other ions

The time profile of the strong SEP proton flux event of November 4, 2001 (from Reames, 2004) is shown in Figure 22. After a steep flux increase within minutes after flare onset, the fluxes in the low energy bands remain about constant for several hours while for higher energies the fluxes gradually drop, i.e., the energy spectra become steeper. Later on, a general flux increase in all channels culminates in a distinct peak that exactly coincides with the passage of the associated shock wave at the observing spacecraft. Even relativistic protons with energies of more than 510 MeV peak at the shock that is driven by a sufficiently fast CME coming from the region near the Sun’s disk center. Generally, the peak proton intensity at shock passage was found to be correlated best with the initial speed of the associated CME (Kahler et al., 1984; Kahler, 2001b). Only the fastest ∼ 1% of CMEs produce significant SEP effects. The longitude difference between the CME source and the observer as well as the angular extension of the shock wave may also affect the local SEP fluxes.

Time profiles of the strong SEP proton flux event of November 4, 2001. The peak at the time of shock passage is clearly defined early on November 6, even at proton energies as high as 510–700 MeV. From Reames (2004).

The realization of large SEP events being driven by CME shock waves rather than by solar flares meant a major paradigm change in the early 1990s (see Reames et al., 1996, and references therein). After all, SEPs may become a tool to probe the shock and topology of the shock. By comparing complete intensity-time profiles of SEPs from several spacecraft one may obtain self-consistent models of the evolving structures.

Figure 23 (from Reames et al., 1996) shows the time profiles of SEP fluxes as seen by observers viewing a large CME shock from 3 different longitudes. The left hand panel shows what an observer located east of the CME will see. Since he is magnetically well connected to some point along the nose shock early on, he will notice a rapid rise of SEPs. The decline is due to the fact that he will be connected with increasingly weaker parts of the eastern shock flank. Another observer stationed near the central meridian will see a slower initial rise since he is connected with the western shock flank. Then, due to a large extended shock front, he is always well-connected until the shock passes: thus, he sees flat profiles (middle panel). An observer located on the western flank of the CME is poorly connected with the distant western shock flank until after the shock passes. Then he is connected (on the backside of the shock) with the powerful nose of the shock and encounters high SEP fluxes for quite some time.

Typical intensity-time profiles for protons of 3 different energies are shown as seen by observers viewing a large CME-driven shock from 3 different longitudes indicated. The observer seeing a western event (left hand panel) is well connected to the nose of the shock early and sees rapid rise and decline. Another observer near central meridian (middle panel) is well-connected until the shock passes; thus, he sees flat profiles. The observer viewing an eastern event is poorly connected until after the local shock passes, when he is on the field lines that connect him to the powerful nose of the shock (from behind). From Reames et al. (1996)

It is now widely agreed that SEPs come from two different sources with different acceleration mechanisms working: The flares themselves release impulsive events while the CME shocks produce gradual events (see the terminology discussion by Cliver and Cane, 2002). The SEPs from flares often have major enhancements in 3He/4He and enhanced heavy ion abundances, because of resonant wave-particle interactions in the flare site. The ions usually have usually very high ionization states. However, the most intense SEP events, also with the highest energies, are produced by CME driven shocks. These SEPs reflect the abundances and ionization states of the ambient coronal material.

The terms impulsive and gradual originally came from the time scales of the associated X-ray events, but nowadays they are applied to distinguish the time scales of SEP events. In fact, the time profiles of impulsive and gradual SEP events look rather different as is shown in Figure 11 of Reames (1999). The gradual event is due to an erupting filament as part of a CME, with no accompanying flare. The impulsive events were associated with several impulsive flares, but without any CME signatures. The gradual event is dominated by protons, with a small peak at shock passage. The smooth and extended time profile comes from continuous acceleration at the moving CME shock. In the impulsive event the electron fluxes are higher than those of the protons and those of the gradual event, respectively. The comparatively short duration of the impulsive event is determined by scattering of the particles as they traverse interplanetary space.

The differentiation between these two types of SEP events is now rather straightforward and unique. Some statistical analyses revealed interesting facts. Reames (1999) compared the “source longitude” of the associated flares for the two types. The distribution of gradual events was found to be almost uniform across the face of the Sun. Determination of a “source longitude” is complicated since many gradual SEP events apparently originated from behind the Sun’s limb, and many CMEs driving gradual SEP fluxes were not associated with flares. After all, there is no doubt about a pretty uniform distribution. In contrast, the impulsive event sources are clearly concentrated in the western half of the Sun with a surprisingly sharp peak at W60. That is about the source longitude of the “average” Parker spiral that connects the Earth to the Sun. Apparently, these impulsive SEPs are injected right into and contained well within “their” flux tube. They do not have much chance to escape to neighboring field lines. The comparison of the distributions indicates that the broad distribution of gradual events can not result from cross-field diffusion, since there is no reason why this same process would not also broaden the distribution of impulsive events. The broad distribution of gradual events suggests the existence of large-scale shock waves that can easily propagate across field lines. The long-standing problem “How can flare-accelerated particles be transported to the often very distant field lines where they are observed?” that had puzzled whole generations of scientists (see, e.g. Kunow et al., 1991) can finally be considered solved.

There is an important implication with respect to space weather effects: The direct injection of impulsive SEPs affects only a narrow regime in space. But the shock fronts driven by CMEs can extend over large spatial angles and thus can fill them with high fluxes of SEPs (Simnett, 2003). In particular, the very big and fast events produce the highly relativistic and most dangerous particles and spread them almost all around the Sun, covering nearly the whole heliosphere.

There is a vast literature on the important issue of elemental abundances in SEP fluxes. Most impulsive flares show not only substantial enhancements of the 3He/4He ratio but also enhanced heavy ion contents, as compared to oxygen (Reames and Ng, 2004). It is thought that these anomalies contain information on the acceleration and propagation processes. These aspects will not be addressed further in this review. The interested reader can easily find (e.g., by searching the ADS) relevant papers by authors such as Reames, Klecker, Cane, Mason.

4.2 SEPs: electrons

The fluxes of non-thermal electrons as products of solar transient processes are very variable and hard to predict (for a general review see Lin, 1985). Apparently, there is a variety of processes to produce these electrons: 1) The energy spectra extend smoothly to the suprathermal range, down to 2 keV, indicating that these events originate high in the corona (Potter et al., 1980). 2) Electrons accelerated at flare sites with a very wide energy spectrum that cause the radio type III bursts as discussed above (Alvarez et al., 1972). 3) Electrons accelerated at the propagating interplanetary shock waves, both upward and downward, leading to the characteristic “herringbone” pattern of radio spectra shown in Figure 19 (Mann and Klassen, 2005).

At low energies below a few tens of keV, the observed electron fluxes may be a mixture of all the mentioned sources. That is probably the reason why spectra in this energy range are so variable and often show several breaks and kinks (see, e.g. Lin, 1985). At higher energies, above a few MeV, the situation changes. Evenson et al. (1984) found that most events with high fluxes of 5 to 50 MeV electrons appear to have been produced by flares which also produced observable fluxes of Gamma-rays. These events are never accompanied by strong interplanetary shocks which therefore are not a source of electron acceleration above a few MeV. It is concluded that the variable nature of the interplanetary particle events must reflect some fundamental but variable property of the shocks — possibly their direction of propagation.

For the very large events, electrons with energies up to 100 MeV have been observed (Simnett, 1974; Moses et al., 1989). The energy spectra are usually rather hard, i.e., with power law indices of 3 and higher. For some events, spectral steepening above a few MeV is observed (Lin et al., 1982). It is not clear yet whether the energy spectrum extends beyond 100 MeV.

There are several open questions concerning the origin and propagation of energetic electrons from flares and shocks. This is illustrated by the recent ongoing controversy about “delayed injection”. The well-known type III burst producing electrons with their typical energies below 30 keV are also directly observed near the Earth. However, some near-relativistic electron events (energies above 30 keV) were released up to 30 minutes later in comparison to the type III radio emission onset. For the origin of this delay three explanations are being debated: 1.) The delayed electrons come from coronal shocks, like the herringbones at type II radio bursts (Krucker et al., 1999; Klassen et al., 2002; Haggerty and Roelof, 2002). 2.) The delayed electrons originate at reconnection site behind the shock front, and the CME shock itself plays only a minor role (Laitinen et al., 2000; Klein et al., 2001; Maia and Pick, 2004). 3.) All electrons originate from a single population, and the delay is due to propagation effects across magnetic field lines (Cane, 2003). Klassen et al. (2005) analyzed the October 28, 2003 flare and found three separate stages of injection. After some detailed analysis and discussion they state: “… the association of the two delayed injections with solar events is not well understood.”

In this context, another potentially relevant issue should at least be mentioned. Several authors recently addressed the appearance of a local minimum and maximum of the local Alfvén velocity in the middle of the corona and at 4 Rs, respectively. That would have effects on the formation of shocks in the corona and interplanetary space as well as the temporal behavior of the associated energetic particle events (Gopalswamy et al., 2001a; Mann et al., 1999, 2003; Vršnak et al., 2004; Warmuth and Mann, 2005).

4.3 SEPs: neutrons

At the biggest flares protons are accelerated to energies of several GeV. Upon interaction with other atoms they cause nuclear reactions that release Gamma-rays and relativistic neutrons. Chupp et al. (1982, 1987) reported the first direct detection of solar neutrons from a satellite-borne instrument following an impulsive solar flare. Identification of the n-p capture line at 2.223 MeV observed at energetic flares confirms the existence of flare-associated neutrons. Combining these observations, it is possible to study the solar neutron energy spectrum from ∼ 1 MeV to several GeV. Ramaty et al. (1983) pointed out that this allows us to investigate the time history of particle acceleration in solar flares and to determine the total number and the energy spectrum of the accelerated ions up to the highest energies.

Due to the absence of charge, solar neutrons can reach the Earth fully unhindered, provided their lifetime is long enough. That is the case only for relativistic neutrons. However, it is difficult to differentiate solar neutrons from those neutrons that are generated in the Earth’s atmosphere. In fact, when a high flux of relativistic SEPs strikes the Earth’s atmosphere, spallation of atmospheric atoms sets on that lets nuclear byproducts cascade down such that enhanced neutron fluxes reach the ground. For monitoring these so-called ground level events (GLEs), a network of neutron monitors has been installed all over the globe, e.g., the “Spaceship Earth” observing network (Bieber et al., 2004). It provides an effective means of studying the angular distribution and energy spectrum of the most energetic SEPs. The problem is that these SEPs and the solar neutrons are generated simultaneously and, thus, should arrive at the Earth almost simultaneously as well.

During the Halloween events three GLEs were observed. Theone on October 28 was of particular interest: About 8 minutes before the main GLE seen by several stations, the one in Tsumeb, South Africa saw a very weak but distinct neutron flux (Bieber et al., 2005), simultaneously with ehe SONG neutron doctor on theCORONAS-F spacecraft (Miroshmchenko et al., 2005), as is shown inFigure 24. Assuming that the first solar neutrons were emitted at the onset of the most conspicuous electromagnetic emissions from the Sun, the travel time to Earth allows an estimate of the neutrons’ energy of 400 to 500 MeV.

Increase profiles of the GLE observed with 5-min averages by Tsumeb and Moscow neutron monitors. The vertical arrow indicates the start of bright radio emission at 1102 UT. The horizontal bar marks the time when neutrons were detected by the SONG instrument at CORONAS-F spacecraft. From Miroshnichenko et al. (2005).

4.4 The accelenration of SEPs